Glottocode: bana1308, ISO 639-3: none

The Bulgarians of the Banat region (Bulgarian: банатски българи, Serbian: банатски бугари, Romanian: bulgari bănățeni), also known as Paulicians (Banat Bulgarian: palćene, standard Bulgarian: pavlikeni, Romanian: paulicheni, German: Paulikaner, less commonly Paulikianer, Paulizianer), belong to the Catholic Church. As the Paulicians were originally a religious grouping that emerged in the Middle Ages, this is likely to be a case of name transfer which must have occurred after the decline of the Bogomils at a time when conversions to Catholicism abounded. The Banat Paulicians were refugees from northern Bulgaria who escaped to the Habsburg empire, in particular after the Turkish suppression of the 1688 Čiprovci Uprising (Steinke 2016), and eventually settled in the villages of Vinga and Dudeştii Vechi (Romania) as well as in several villages on Serbian territory, notably Ivanovo (Kálápiš 2014: 111). While some of the Paulicians live in Bulgaria – a southern group settled around Plovdiv and a northern one around Nikopol on the Danube – the part of the group to be discussed here lives in the Banat region. Their separate Banat Bulgarian language was able to achieve the status of a literary microlanguage due its early alphabetization using the Latin alphabet.

Settlements represented in our collection

Read more...

Read more...

The geographic spread of the Bulgarian language covers a much wider area than just Bulgaria: In Ukraine and Moldova, Bessarabian Bulgarian is common, as are Banat Bulgarian in the Romanian and Serbian Banat region and Wallachian Bulgarian in Romania's Wallachia; furthermore, Bulgarian speakers live in Hungary, Greece and the more recent countries of immigration of Western Europe and America.

Emigrations from Bulgaria and settlements on Romanian soil have been taking place since the 14th century and, as a background, they mostly had uprisings or wars that forced people to migrate north of the Danube. For intellectual and political reasons, they were also induced to settle in the Romanian principalities. The Wallachian Prince Michael the Brave (1558-1601) resettled more than 26,000 Bulgarians north of the Danube at the end of the 16th century (Karabencheva 2009: 57). In the 18th and 19th centuries, other emigration flows are recorded, targeting Wallachia, Ukraine, Bessarabia and Moldova (Kahl 2013: 266). The Bulgarians of Southern Romania, apart from the Catholics in Popeşti-Leordeni, are Orthodox denominations and for the most part can be considered as linguistically assimilated, although they may still be considered active through cultural events (Grasu 2000).

The Bulgarians of the Banat region (Bulgarian: банатски българи, Serbian: банатски бугари, Romanian: bulgari bănățeni) are also known under the name of Paulicians (Banat Bulgarian: palćene, standard Bulgarian: pavlikeni, Romanian: paulicheni, German: Paulikaner, less commonly Paulikianer, Paulizianer) and belong to the Catholic Church. As the Paulicians were originally a religious group that emerged in the Middle Ages, this is likely to be a case of name transfer which must have occurred after the decline of the Bogomils at a time when conversions to Catholicism abounded. The Banat Paulicians were refugees from northern Bulgaria who escaped to the Habsburg empire, in particular after the Turkish suppression of the 1688 Čiprovci Uprising (Steinke 2016), and eventually settled in the villages of Vinga and Dudeştii Vechi (Romania) as well as in several villages on Serbian territory, notably Ivanovo (Kálápiš 2014: 111). Along with the Independence of Bulgaria and the development of a national spirit towards the newly founded Principality in 1877 (Njaguov 2009: 47), some of the Banat Bulgarians have made their way to Bulgaria where a southern group settled around Plovdiv and a northern one around Nikopol on the Danube. To this should be added the consequences of the 1940 Treaty of Craiova that began the resettlement of around 60,000 Bulgarians from northern Dobruja to Bulgaria (Sallanz 2005: 16) – a population transfer that did not, however, affect the Banat Bulgarians.

The Banat Bulgarians in today's Romanian Banat reside in the villages Dudeștii Vechi (2439 residents), Vinga (333 residents) as well as Breștea, Denta and Deta (around 500 Bulgarians in all three taken together), in Temesvar (859) and Arad (180) (INDS 2011). Due to their common language, they are often examined and described as an ethnically homogeneous group (cf. e.g. Nomachi 2016a; Nomachi 2016b).

In terms of language maintenance in multi-ethnic Banat of the 18th and 19th century, religion played no lesser role than oral tradition did for immaterial culture and traditional costumes, and mores and customs for material culture. Due to the promotion of schooling and education, expansionist Catholicism was well able to conserve the coexistence of the languages and dialects used by the various ethnic groups, independent of the respective political circumstances. The mosaic of multi-confessional Banat, dominated by Hungarian- and German-speaking inhabitants for a long period of time, was in addition now increasingly settled by Serbs and Romanians, as well as Italians and Frenchmen beginning in the 18th century (for more detail cf. Wolf 2004), while Theresian religious policy had language-maintaining effects on most ethnic groups.

The Banat Bulgarian language was able to achieve the status of a literary microlanguage due its early alphabetization using the Latin alphabet. Franciscans and Jesuits already settled in Banat during the Ottoman reign as pastors and teachers. Before the building of new churches, they often remained in the old mosques, before erecting their own sacral buildings in many towns of Banat (Arad, Carașova, Radna, Lugoj and Vinga) and leading their own communities. Their missionary work was accompanied by the opening of schools and followed the model of the so-called schola latina that continued to have an effect even during the Enlightenment and the science policy of the 18th century (Winter 1976: 87f.). Many multi-ethnic villages were under ecclesiastical administration and offered private schooling. Only this way, education could be conducted in the native language or in several languages (Rieser 2001: 153). In the past, the Catholic Church has played the key role in maintaining the Banat Bulgarian language. Even today, it considers itself the preserver of the linguistic heritage of the Banat Bulgarians whose education in their own language was promoted beginning in the mid-19th century.

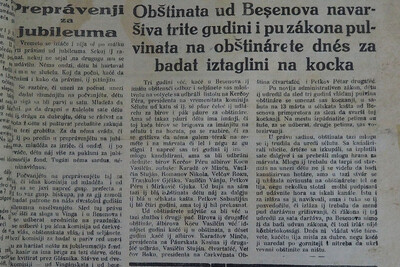

The language in its current form is a blend of elements of the Southwestern Rhodope dialect that was brought along with the Paulican Bulgarians, and of Northwestern Bulgarian elements such as could be found in the dialect of the Chiprovtsians (Duličenko 2002: 204; Стойков 1967: 23). The prayer books of Croat priest Andrej Klobučar (Hungarian: Andria Klobucsár) who lived in Beschenowa were, on the other hand, strongly influenced by Croatian. In 1866, Vinga teacher Jozu Rill suggested an alphabet that was later not adopted in its original form either, the more so as Rill used different graphemes to represent the same sound (Duličenko 1998: 328). Today, a simplified alphabet has become widely accepted that follows these traditions in part and is more or less consistently used in most of today's publications (e.g. in Markov 2013; Vasilčin 2012). And though the Banat Bulgarians have succeeded in developing their own literary language using the Latin alphabet, today it is mainly used in a church-related context.

In 2011, 7,336 persons in Romania declared themselves Bulgarians, which is an enormous decline compared to 66,348 in 1930 (INDS 2011). These low numbers of Bulgarians living in Romania can be attributed to the waves of emigration beginning in the late 19th century. The Bulgarian national revival was also driven by the Bulgarian intelligentsia residing in the Romanian United Principalities, as a Bulgarian national consciousness or at least a perceived relationship to the Principality of Bulgaria, founded in 1877, developed among them (Njagulov 2009: 47). Coupled with the fear of Romanian assimilation, this led to the emigration of many Bulgarians from Romania „back“ towards Bulgaria, where Bădarski Geran became the main place of settlement for Bulgarians from Dudeşti and Asenovo for those from Vinga (Karabencheva 2009: 78). To this should be added the consequences of the 1940 Treaty of Craiova that began the resettlement of around 60,000 Bulgarians from northern Dobruja to Bulgaria (Sallanz 2005: 16) – a population transfer that did not, however, affect the Banat Bulgarians.

The Banat Bulgarians in today's Romanian Banat reside in the villages Dudeștii Vechi (2439 residents), Vinga (333 residents) as well as Breștea, Denta and Deta (around 500 Bulgarians in all three taken together), in Temesvar (859) and Arad (180) (INDS 2011). Due to their common language, they are often examined and described as an ethnically homogeneous group (cf. e.g. Nomachi 2016a; Nomachi 2016b).

The year of 1989 triggered a kind of renaissance in the Banat Bulgarians' self-perception that also propagated a more confident external positioning using folklore performances. Their isolated location of settlement far from their origins in Bulgaria might have also contributed to this development. Due to the significant Banat Bulgarian literary tradition, it is now considered a literary microlanguage. This is defined by Duličenko (2006: 27) as „a form of an existing language (or dialect), which has been used in written texts and is characterised by normalising trends emerging as a result of the functioning of the literary writing form within the framework of a more or less organised literary and linguistic process.“Only few linguistic minorities in the Southeast of Europe have accomplished equipping their language with a written form. And though their literature has contributed significantly to the manifestation of their contemporary patterns of identity, the Banat Bulgarian language remains endangered.

Bibliography

Bibliography

- Berger, Tilman (2017): Versuch einer Annäherung an das Banater Bulgarische, und speziell an seine Orthographie. In: Meyer, A.-M.; Reinkowski, L.: Im Rhythmus der Linguistik. Festschrift für Sebastian Kempgen zum 65. Geburtstag. Bamberg: University of Bamberg Press: 59-76.

- Buruleanu, Dan N.; Cociuba, Victor (2010): Vinga. Istorie și imagini. Timişoara, Tipar.

- Décsy, Gyula (1959): Die ungarischen Lehnwörter der bulgarischen Sprache. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Duličenko, Alexandr (1998): Das Banater Bulgarisch. In: Rehder, Peter (ed.): Einführung in die slavischen Sprachen, Darmstadt, 326-330.

- Duličenko, Alexandr (2002): Banater Bulgarisch. In: Okukua, Miloš (ed.): Lexikon der Sprachen des Europäischen Ostens, Klagenfurt: Wieser, 203-208.

- INDS (2011): Institutul Național de Statistică: Rezultate definitive. Populația stabilă (rezidentă). Structura etnică și confesională

- Ivanciov, Margareta (2009): Istorijata i tradicijite na balgarskotu malcinstvu ud Rumanija. Ucebnic. Timisoara: Mirton.

- Kahl, Thede; Pascaru, Andreea (2017): Das Banater Bulgarisch im Dialog mit der Vergangenheit: Zur sprachlichen und kulturellen Identität einer slawischen Minderheit. Bulgarica (München) /1, 101-131. Book order

- Kálápiš, Áugustin (2014): 145 godina od doseljavanja banatskih Bugara-Palćena u Ivanovo. Temišvár: Mirton.

- Karabencheva, Katerina (2006): La minorité bulgare de Roumanie: entre conservation de l’identité ethnique et emergence de la représentation politique après 1989. In: Studia Politica. Romanian Political Science Review 3, 617-633.

- Karabencheva, Katerina (2009): Istoria minorităţii bulgare. In: Zsolt, Jakob Albert; Lehel, Peter (Hg.): Procese și contexte social-identitare la minorităţile din România, Cluj-Napoca: Kriterion (Editura Institutului pentru Studierea Problemelor Minorităţilor Naţionale), 51-100.

- Király, Péter (2008): Orthografie und Sprache der Banater bulgarischen Bücher. Studia Slavica Hungarica 53/2, 375-380.

- Markov, Nicolae (2013): Publicațiile periodice ale bulgarilor bănățeni - scurtă prezentare. The regular publications of the Bulgarians from Banat - short presentation. In: Carmina balcanica 5/1 (10), 86-102.

- Mladenova, Marinela (2014): Slavic Literary Microlanguages Amid Internationalisation Trends (Based on Examples from the Codified Language of the Banat Bulgarians). In: Mundo Eslavo 13, 63-73.

- Njagulov, Blagovest (2009): Trecutul și prezentul comunității bulgare. In: Zsolt, Jakab Albert; Lehel, Peti (Hg.): Procese și contexte social-identitare la minoritățile din România, Cluj-Napoca: Kriterion; Editura Institutului pentru Studierea Problemelor Minorităţilor Naţionale, 41-52.

- Nomachi, Motoki (2016a): The Rise, Fall, and Revival of the Banat Bulgarian Literary Language: Sociolinguistic History from the Perspective of Trans-Border Interactions. In: Kamusella, Tomasz; Nomachi, Motoki; Gibson, Catherine (ed.): The Palgrave Handbook of Slavic Languages, Identities and Borders, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 394-428.

- Nomachi, Motoki (2016b): Whose Literature? Aspects of Banat Bulgarian Literature in Serbia. In: Abe, Kenichi (Hg.): Perspectives on Contemporary East European Literature: Beyond National and Regional Frames, Sapporo: Slavic-Eurasian Research Center, 179-192.

- Pascaru, Andreea (2016): Sprachliche und kulturelle Identität in einer multiethnischen Region: Die Banater Bulgaren. Masterarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Master of Arts (MA). Jena: Friedrich-Schiller-Universität (unpublished Master thesis).

- Rieser, Hans-Heinrich (2001): Das rumänische Banat - eine multikulturelle Region im Umbruch. Geographische Transformationsforschungen am Beispiel der jüngeren Kulturlandschaftsentwicklung in Südwestrumänien. Schriftenreihe des Instituts für donauschwäbische Geschichte und Landeskunde 10, Stuttgart: Jan Thorbecke.

- Stantchev, Krassimir (2011): I francescani e il cattolicesimo in Bulgaria fino al secolo XIX. In: Nosilia, Viviana; Scarpa, Marco (Hg.): I francescani nella storia dei popoli balcanici nell'VII centenario della fondazione dell'Ordine. Atti del convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia, 13-14 novembre 2009 (I Balcani tra Oriente e Occidente), Bologna: Centro Interdipartimentale di Studi Balcanici e Internazionali, Archetipo Libri, 139-186.

- Steinke, Klaus (2006): Zur Vitalität bulgarischer Minderheiten in Rumänien. In: Stern, Dieter; Voss, Christian (Hg.): Marginal linguistic identities (Eurolinguistische Arbeiten), Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 75-85.

- Steinke, Klaus (2016): Paulikianer. In: Enzyklopädie des europäischen Ostens online

- Vasilčin, Jáni (2012): Banátsćija balgarsći dialekt i pismenus. Stár Bišnov: Rimska-katoličánska Biskupija.

- Vasilcin, Ioan et al (2006): Monografia localității Dudeștii Vechi, Jud. Timiș, Timișoara: Mirton.

- Winter, Eduard (1976): Die katholischen Orden und die Wissenschaftspolitik im 18. Jahrhundert. In: Amburger, Erik; Ciesla, Michal; Sziklay, Laszlo (Hg.): Wissenschaftspolitik in Mittel- und Osteuropa. Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaften, Akademien und Hochschulen im 18. und beginnenden 19. Jh., Berlin: Ulrich Camen, 85-96.

- Wolf, Josef (2004): Entwicklung der ethnischen Struktur des Banats 1890-1992. Begleittext. Österreichisches Ost- und Südosteuropa-Institut: Atlas Ost- und Südosteuropa 2.8 - H/R/YU 1, Stuttgart: Borntraeger.

- Гегова, Илияна (2019): Социолингвистични аспекти на Банатския говор. In Факултет по славянски филологии Катедра по български език, 42. София: Софийски унижерситет „Св. Климент Охридски“

- Дуличенко, Александр Д. (2006): Современное славянское языкознание и славянские литературные микроязыки. In: Дуличенко, Александр Д.; Gustavsson, Sven; Dunn, John A. (Hg.): Славянские литературные микроязыки и языковые контакты: материалы международной конференции, организованной в рамках Комиссии по языковым контактам при Международном Комитете славистов Тарту, 15-17 сентября 2005 г (Slavica Tartuensia 7), Tartu: Tartu University Press, 22-46.

- Карабенчева, Катерина (2006): "Етнокултурна идентичност на банатските българи в Румъния." Български фолклор 1, 74-80.

- Нягулов, Благовест (1998): "Българското малцинство в Югославски Банат под германска окупация (1941-1944)". Балканистичен Форум 1-3, 87-101.

- Нягулов, Благовест (1999): Банатските българи. Историята на една малцинствена общност във времето на националните държави. София, Парадигма.

- Младенова, Маринела (2017): "Към историята на книжовното наследство на банатските българи: “Pulgarsćite Právici i Dlažnusti za sêku dumovin pulgar i negvata mladina u Madžársku” ud Leopold Kossilkov u Vinga (1888) (Или за първите опити за създаване на юридическа терминология на банатски български език)." Балканистичен Форум. Balkanistic Forum 3/17: 119-134.

- Парашкевов, Борис (2007): Немски елементи в говора на банатските българи. София: Университетско Издателство Свети Климент Охридски.

- Стойков, Стойко (1967): Банатският говор. Трудове по българска диалектология 3, София: Издателство на Българската академия на науките, Институт на български език.

- Стойков, Стойко (1968): Лексиката на банатския говор. София: Издателство на Българската академия на науките, Институт на български език.

Video collection

PHOTO COLLECTION

Links

Virtual Library of Banat Bulgarians

Banat Bulgarian Union of Romania

Banat Bulgarian Blog "Sveta ud pukraj námu"

Association of Banat Bulgarians in Sofia

© Thede Kahl & Andreea Pascaru 2019