Because of his fondness for German legends and heroic stories, Emperor Maximilian I has been given the nickname "the last knight". In 1504, he commissioned the "Ambraser Heldenbuch" ("The Ambras Castle Book of Heroes"), the largest collection of medieval German literature bequeathed to us. In addition to "Kudrun" and "Nibelungenlied", the richly illustrated manuscript contains a dozen texts that would have been lost were it not for a tollkeeper from Bolzano, who, by order of the Emperor, spent 12 years of his life putting them in writing. In 2019, on the occasion of the 500th anniversary of the death of Emperor Maximilian, the "Ambraser Heldenbuch" is to be revived in an online edition.

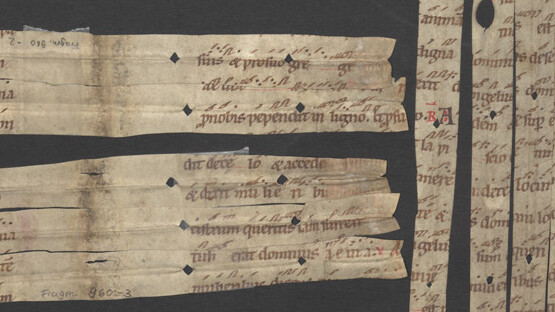

But until then, there is still a lot of research and transcription work to do. With 500 large parchment pages and 500,000 words, the "Ambraser Heldenbuch" is a literary heavyweight. But the undertaking is worthwhile, says Mario Klarer, head of the project and literary scholar at the University of Innsbruck. The complete transcription of the Book of Heroes has been a central research gap for many years. Thanks to a "go!digital" grant from the Austrian Academy of Sciences (OeAW), this gap can now be filled.

The "Ambraser Heldenbuch" was written by a tollkeeper from Bolzano by order of Maximilian I. Why did the Emperor not hire a professional clerk at Court for this major project?

Mario Klarer: Hans Ried, the scribe of the "Ambraser Heldenbuch", was both a tollkeeper and a professional chancery clerk. In 1496, the Emperor granted him an annuity for life for his faithful service in the royal chancery, and from 1500 he held the office of tollkeeper on the Eisack river.

The emperor commissioned Hans Ried to transcribe the stories in 1504. How long did he work on the 243 ornate double-sided parchment pages?

Klarer: Until his death in 1516. He exercised his duties as a tollkeeper partly parallel to the work on the Book of Heroes, but was also regularly allowed time to concentrate entirely on the book. Unfortunately, we do not know which templates Ried used, or whether other texts were originally intended for the collection. Only after Ried's death in 1517 were the illuminations, the decorative pictures, added to the book.

Ried's patron, Emperor Maximilian, is also popularly called the "last knight": his interest in German knight and hero stories went far beyond this project, right?

Klarer: Maximilian had always been interested in history. He studied, for example, the frescoes of the South Tyrolean castle Runkelstein, which portray literary figures such as Tristan and Isolde. In 1519 he also commissioned the publication of "Theuerdank", which is similar in structure to a courtly epic. Maximilian's adoration for knightly heroes is also reflected in the design of his own tomb. King Arthur and Theodoric the Great, both heroic figures who found their way into literary texts, are amongst the figures that line the Emperor’s cenotaph in the Court Church in Innsbruck.

After its completion, was the lavishly designed "Ambraser Heldenbuch" actually "read" in the modern sense?

Klarer: We do not know. There is not even a documentary mention of where the book was kept in the first decades after completion. It is first listed in a 1596 inventory of the Chamber of Art and Curiosities at Ambras Castle, after which it is currently named. In 1806, when it was feared that Innsbruck might be occupied by French troops, the art collection of Ambras Castle, including the book, was brought to Vienna. There it stayed in the Belvedere until 1936, when it was moved to its current location, the Austrian National Library.

But for the 500th anniversary of Maximilian I's death in 2019, the original will finally be presented to a wider audience.

Klarer: Yes – in the Golden Roof and the Hofburg in Innsbruck, there will be a digital-haptic installation, in which a reprint of selected pages will be exhibited and supplemented with information by means of projection. A popular science anthology for the book is also in preparation. Germanists or medievalists will be interested in the online transcription of the entire book and the results of the research project, which will be published online after its completion. But it will also be possible to form your own impression of the book from high-resolution scans of the original pages.

Do you have a favorite among the 25 texts contained in the book?

Klarer: My favorite text is "Meier Helmbrecht" from the second half of the 13th century. In this story, the author, Wernher der Gärtner, describes Helmbrecht, a farmer's son, who in his stupidity wants to be a knight. Helmbrecht's presumptuous clothing includes an embroidered cap, which is described at the beginning of the text in more than a hundred verses. This unusually detailed description was long an unsolved mystery in "Helmbrecht" research. By chance, in the 1990s, I came up with the idea that the depictions on the cap could symbolize what is inside Helmbrecht's head: the mind of a fool.