by Nurlan Kabdylkhak, University of North Carolina

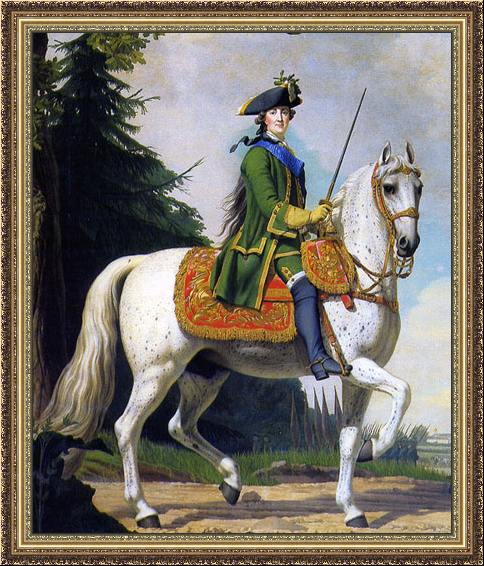

Catherine II stands out as one of the most consequential rulers in Russian history. Her reign, spanning from 1762 to 1796, marked an era of active westernization and modernization across the vast Tsarist empire. Catherine’s profound influence extended to such crucial domains as administration, education, and the legal system. Furthermore, the Russian empress significantly broadened the territorial boundaries of the Tsarist state by annexing the Crimean Khanate and significant portions of Poland.

Beyond her political achievements, Catherine II earned a reputation as a dedicated patron of the arts and culture. She played a crucial role in fostering the development of literature, theater, and the fine arts, turning her court into a vibrant center of intellectual and cultural activity. Catherine II was not only known for her intellectual pursuits but also distinguished herself as a prolific writer, contributing extensively to the realms of letters, playwriting, and memoirs. Her correspondence with Enlightenment thinkers and writers, including the famed Voltaire, spanned many years and is now considered a valuable historical and literary resource. Additionally, Catherine’s literary legacy includes two lesser-known “fairy tales” crafted for her grandson, the future Russian emperor, Alexander I. In this blog post, I offer a brief discussion of one of these tales and several literary works inspired by it.

Catherine II composed her tales as didactic pieces, aiming to instill in her grandson the virtues befitting a great ruler. She titled her first work “The Tale of Prince Khlor” (Skazka o Tsareviche Khlore) projecting the image of the tsarevich onto her grandson, Alexander. The narrative unfolds in ancient times, predating the legendary founder of Kyiv, Kiy, as emphasized by Catherine. The central figure is Prince Khlor, born to a benevolent Russian tsar. The prince’s exceptional qualities gained him fame beyond Russia even in his youth. Soon news of his beauty and intelligence reached the Qazaq khan (Kirgizskiy khan), who, captivated by Khlor, sought to bring him to the steppe. Attempts to sway the prince’s nannies with gifts failed, prompting the khan to disguise himself as a beggar and personally abduct Khlor. The khan transported the Russian prince to his nomadic encampment (kochev’e) and placed him in a tent richly adorned with “Chinese red damask fabric” and “Persian carpets.” To the surprise of the Qazaq ruler and his subjects, Khlor exhibited a respectful demeanor. Impressed, the khan set forth a challenging task for Khlor – finding a “rose without thorns.”

Khlor embarked on his quest, encountering a kind woman along the way, revealed to be Qazaq khan’s daughter, Khansha Felitsa. Touched by the young Russian’s noble character, Felitsa decided to aid him. Despite the Qazaq khan’s reluctance, Felitsa generously shared her wisdom, warning Khlor of potential distractions along his journey. She cautioned him against succumbing to temptations of “fun and joyous time” (vesel’ya i zabavy) suggested by others, urging him to remain steadfast in pursuit of his true purpose. Additionally, Felitsa pledged to send her son, Rassudok (Rus: Reason), as Khlor’s companion.

During their arduous journey, Khlor and Rassudok confronted numerous obstacles, encountering attempts to divert them. Rejecting invitations and resisting distractions, they pressed on. Notably, they spurned an invitation from Lentiag-murza (derived from the Russian word lentiay, meaning lazybone), who enticed the young men with a smoking pipe and coffee. The negative portrayal of coffee consumption in the narrative should not come as a surprise. It aligns with the broader debates of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe, where coffee was often denounced as the “devil’s drink,” believed to transform Europeans into “Turks,” reflecting the Ottoman influence in introducing coffee culture to the continent.

Khlor and Rassudok’s travels brought them into contact with kind peasants and drunken revelers, culminating in an encounter with an elderly couple who bestowed canes named Chestnost’ (Rus: Honesty) and Pravda (Rus: Truth) on the young men. Supported by these symbolic canes, Khlor successfully reached the elusive thornless rose, carrying it back to the Qazaq khan. Impressed by this achievement, the khan graciously permitted Khlor to return home with the precious flower.

While Catherine II’s fascination with the Qazaqs might appear coincidental, implying that their role in the narrative could be filled by other “wild” nomadic peoples within Russia’s vast lands or its surroundings. One could argue that prince Khlor might have been abducted by a Bashkir or Noghay ruler instead of a Qazaq khan without altering the essence of Catherine’s tale. The inclusion of Qazaq characters in the narrative is far from surprising. During Catherine’s reign, Russia aggressively extended its influence over the Qazaq steppe, resulting in an increasing number of Qazaq sultans and their communities becoming Russian subjects. Notably, several Qazaq envoys attended Catherine’s coronation in Moscow in 1762 and were granted an audience with her. Demonstrating her commitment to the multicultural character of her empire, the Russian empress even commissioned the depiction of Qazaq envoys, alongside other “Asiatic peoples,” in her coronation album. Unfortunately, this ambitious project remained unfinished and unpublished.

In 1781, the “Tale of Prince Khlor” was printed as a book. Assessing the tale’s popularity and its reception among the Russian public proves challenging. Nevertheless, the narrative featuring Tsarevna Felitsa garnered immense popularity, prominently propelled by a poem penned by one of the most prominent Russian literary figures of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries – Gavriil Derzhavin. Needless to say, that Derzhavin drew inspiration for his poem from Catherine’s original tale.

Composed in late 1782, Derzhavin’s poem made its debut in 1783, gracing the inaugural issue of the journal “Companion (Sobesednik) of the Lovers of the Russian Word.” The poem’s lengthy title “Ode to the Wise Kirgiz-Kaisak Tsarevna Felitsa, Written by a Tatar Murza, Who Has Long Settled in Moscow but Living on Business in St. Petersburg. Translated from the Arabic Language in 1782,” presumably added by the journal’s editor, Princess Dashkova, provides insight into prevailing Russian stereotypes about Muslims, suggesting their universal proficiency in Arabic.

Derzhavin’s poem expands upon Catherine II’s narrative involving Qazaq princess Felitsa and Tsarevich Khlor. However, the poet redirects the spotlight exclusively onto the tsarevna. The entire composition takes the form of an appeal from the author, identifying himself as a Qazaq murza (Turkic: nobleman), to the “God-like Qazaq princess Felitsa.” In the poem, the murza implores Felitsa, renowned for her “incomparable wisdom,” for guidance “on how to live magnificently and honestly.” Reflecting on his own vices and weaknesses, such as “sleeping until noon,” “smoking and drinking coffee,” indulging in excessive eating of various meals, including “plov,” consuming wine and champagne, spending time with a beautiful young girl (mladaia devitsa), and generally “making a celebration” out of every ordinary day, the murza paints a vivid portrait of his personal struggles that serve as a contrast to the tsarevna’s qualities.

It comes as no surprise that Derzhavin’s poem draws heavily on the characters of the Qazaq khansha addressed by a Qazaq nobleman. On one hand, it continues the narrative line established in Catherine’s tale. On the other hand, Derzhavin’s own background significantly shapes the content of the poem. Gavriil Derzhavin hailed from a noble Russianized “Tatar” family, tracing its roots to “Bagrim-murza” (Ibrahim), who, according to the poet, departed the Golden Horde and settled in Moscow in the second quarter of the fifteenth century. Moreover, as Derzhavin himself later explained later, he owned several estates in the Orenburg province, situated “next to the Kirgiz Horde,” indicating his profound familiarity with the Qazaqs.

It’s worth noting that in the late eighteenth century, Orenburg emerged as Russia’s “Gateway to Asia.” It played a pivotal role, functioning as a crucial political, administrative, and commercial center on the northern fringes of the Qazaq steppe, where the tsarist state interacted with Qazaqs and other Inner and Central Asian Muslims. Originally built in the 1730s in response to a request from Qazaq khan Abulkhair, Orenburg retained its political significance throughout the final years of the Russian empire. Under the Bolsheviks, in 1920, it briefly served as the inaugural capital of the Qazaq Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.

Derzhavin’s poem made a significant impact among the educated Russian public. Within days of its publication, Derzhavin received a remarkable package accompanied by a note that read: “From Orenburg. From Kirgiz Tsarevna to Murza.” Sent by the empress herself, the package contained a gold snuff box adorned with diamonds and filled with 500 gold coins (chervonets). This lavish reward served as a clear testament to Catherine II’s appreciation for Derzhavin's latest poem and his literary talent. This auspicious event advanced Derzhavin’s career to new heights, both as a poet and a statesman in the service of the empress. The poem not only solidified his standing as one of Russia's preeminent poets but also garnered numerous dedications from fellow writers and poets, who affectionately and respectfully referred to him simply as “murza.”

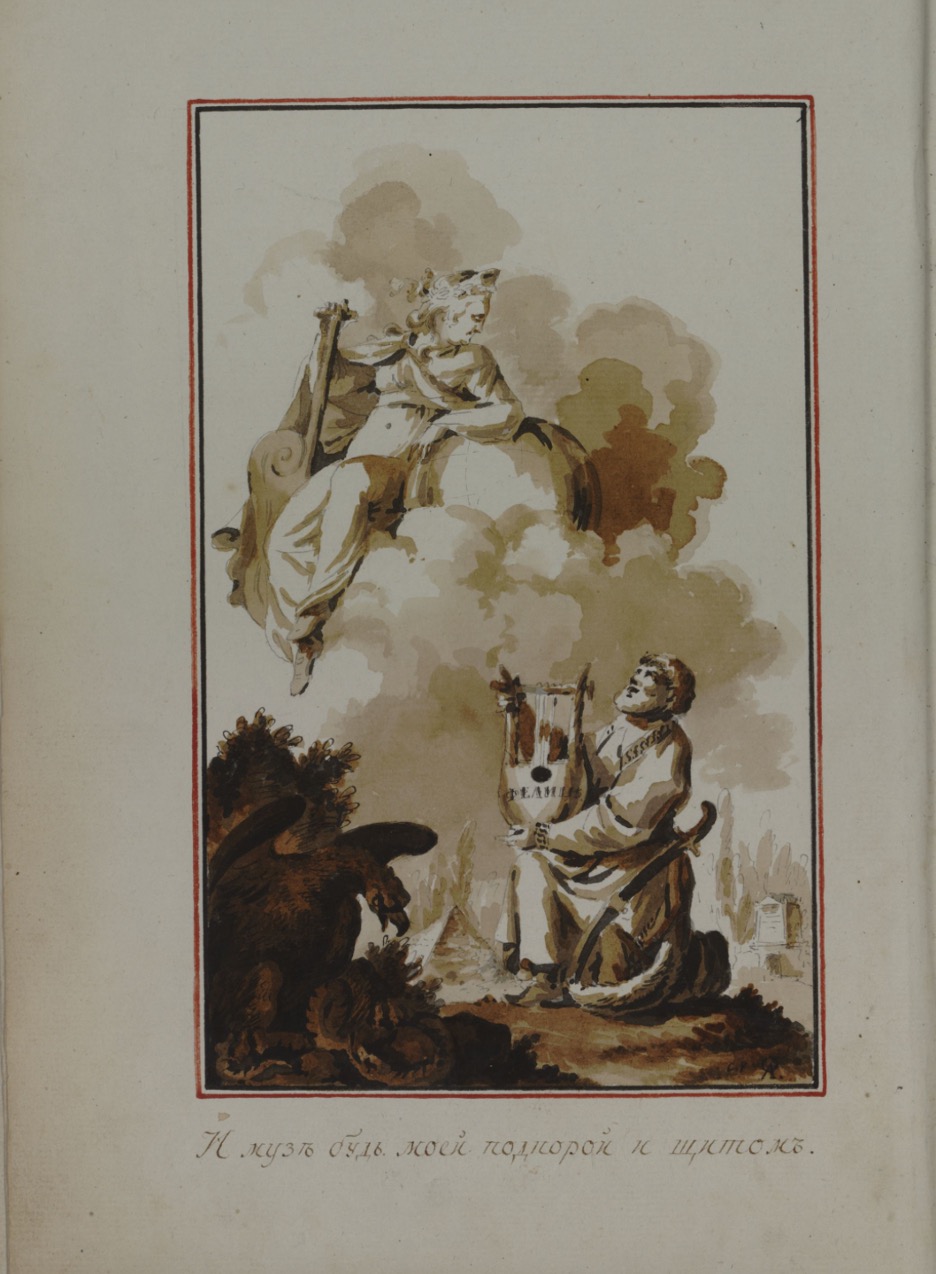

The earliest illustrations created for Derzhavin’s poem deserve a separate exploration, as they offer a unique visual perspective on Qazaq khansha Felitsa and her poetic admirer. These illustrations are discovered in the handwritten manuscript of Derzhavin’s initial collection of poems, later replicated in the published text. The manuscript, personally signed by the author, was Derzhavin’s gift to the renowned Russian bibliophile and diplomat Peter Dubrovsky. In the initial drawing preceding the manuscript’s text, a murza is depicted kneeling before a woman, presenting her with his lyre, symbolizing Derzhavin’s literary creations. The lyre bears the inscription “Felitsa.”

One can spot that the Qazaq murza is portrayed wielding a curved sword closely associated with Muslim cultures. Derzhavin’s explanation in his work “Ob’iasneniia” clarifies that the “Kirgiz murza” in the drawing represents the author himself, while the “Kirgiz tsarevna” symbolizes Catherine II. In the image, the Russian empress is elevated on a throne crafted from clouds, with her right hand resting on a staff and her left on half of the globe.

In the first of the two drawings accompanying the ode in the manuscript, Qazaq princess Felitsa is shown conversing with Tsarevich Khlor while gesturing towards a Parthenon-like temple.

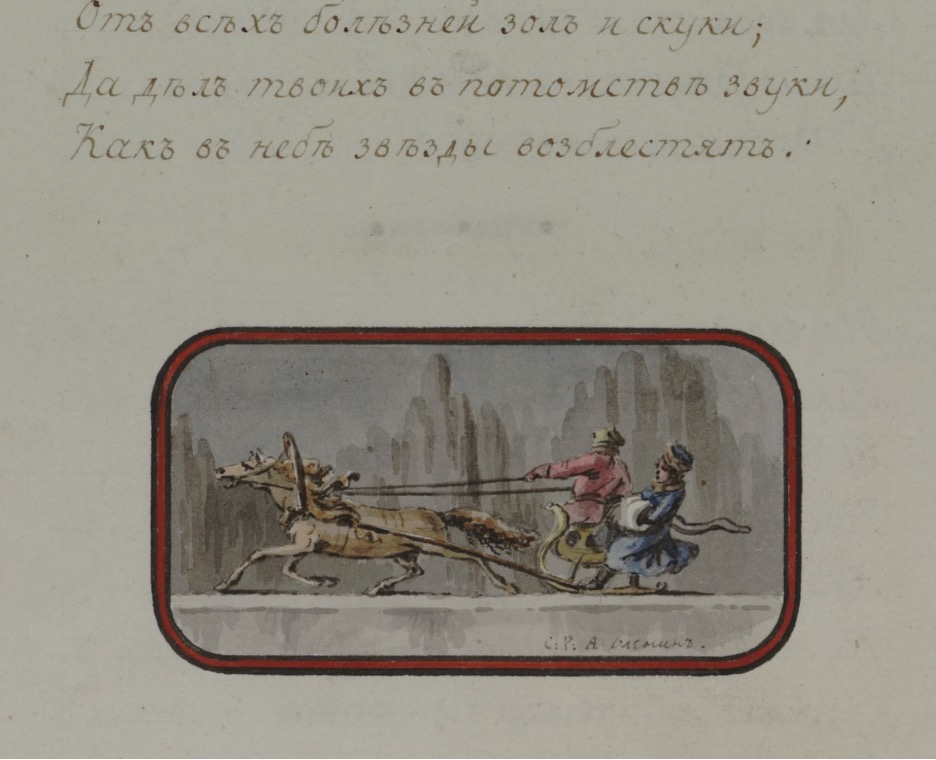

Another drawing portrays “Kirgiz murza” Derzhavin running on a sleigh, seemingly accompanied by Felitsa at his side. Despite the allegorical nature of these illustrations, reminiscent of Catherine’s tale and Derzhavin’s poem, they strangely mark one of the earliest visual representations depicting Qazaqs for the popular Russian readership.

One of the later dedications to Derzhavin’s ode appeared in the city of Kazan in 1815, several years after Catherine’s death and a year before Derzhavin’s passing. Composed by Nikolay Ibragimov, this poem redirects its focus to Khlor, who, in Ibragimov’s imaginative realm, emerges as Felitsa’s grandson and a Qazaq ruler. The poem bears the title “On the Joyful Birthday of Kirgiz-Kaisak Tsarevich Khlor”. Diverging from Derzhavin’s treatment, which briefly acknowledges Felitsa’s Qazaq origin, this poem delves more profoundly into Khlor’s Qazaq identity, along with his broader Muslim and Central Eurasian heritage.

In Ibragimov’s verses, Khlor, now at the age of 37, rules the “Golden Horde,” a fascinating association in itself. Tracing his ancestry back to Zoroaster, Khlor is portrayed as an enlightened ruler, bringing “light” to his community, with people recognizing a prophet in him. He successfully introduces reason and refinement to his people, who now engage not only in “looking in the Quran” but also in creative pursuits, such as composing poems “all over the ulus” (Turkic: country or people). Additionally, Khlor is credited with erecting a temple in the stan (Persian, later adopted to Russian: camp or country) of the Golden Horde, serving as a hub for young men to acquire knowledge in the realms of “unknown” sciences (nauk tarabarski sklady).

It is particularly interesting that the author of this poem, Nikolay Mikhailovich Ibragimov, shares a background similar to Gavriil Derzhavin. Much like the esteemed poet, Ibragimov belonged to a family with roots tracing back to a Muslim ordynets (Rus: horde man) named Ibrahim. A graduate of Imperial Moscow University and subsequently a professor at Imperial Kazan University, Ibragimov published the poem in the proceedings of the “Celebration of the Kazan Society of the Lovers of the Russian Word,” an institution that he himself founded. Adding to the intrigue, Nikolay Ibragimov is recognized as the author of the one of the most well-known Russian folk songs “There was a birch tree in the field” (Vo pole bereza stoiala).

The enduring legacy of the “Tale of Prince Khlor” and its subsequent adaptations highlights the profound impact of Catherine II’s reign, both in terms of her political achievements and her cultural contributions. The works inspired by Catherine’s tale, exemplified by Derzhavin’s ode and Ibragimov’s poem, not only perpetuate her narrative but also add their own unique layers of interpretation and cultural nuances. Furthermore, these works, along with the ethnic backgrounds of their authors, reflect the intricate dynamics of the burgeoning Russian empire and its multicultural subjects, including the Qazaqs and other Muslim minorities under the tsarist rule.