Abdulla Qahhor’s Tales from the Past

by Christopher Fort, American University of Central Asia

Just two years before his death due to complications from diabetes, Uzbek author Abdulla Qahhor published his literary autobiography, Tales from the Past (1966), the culmination of a multidecade project to cement himself in the Soviet Uzbek public’s imagination as a vigilant communist and witness to the cruelty of the pre-Soviet past. This episodic novella presents the author as a sharp-sighted writer capable of revealing harsh truths that both justify and call on audiences to defend the Soviet present. Qahhor was born around the Ferghana valley city of Kokand in 1907, the son of an itinerant blacksmith, who, as Qahhor tells it in his Tales from the Past, was repeatedly cast out of various communities around Kokand for his progressive, ur-Soviet views. In the late 1920s, thanks to his time as a Komsomol leader in Kokand, Qahhor joined the ranks of the new Soviet Uzbek intelligentsia, a cohort who gained their positions thanks to the Soviet purges of their predecessors. Many of those predecessors had been Jadids, Muslim reformers of the late Russian Empire. Over the 1930s and 1940s, Qahhor survived Stalin’s Great Terror (1936-1938) to become a celebrated writer of short stories and satirical comedies. He achieved this fame despite the initial successes and ultimate denunciations of his two novels of Stalin’s lifetime, Mirage (1934) and The Lanterns of Qo‘shchinor (1949).

Qahhor reached those heights, in part, because in the 1950s and during the Thaw, he began to pivot his literary success toward creating a place for himself in contemporary Uzbekistan’s pantheon of writers. My recent research, which I hope to publish soon, shows that with Stalin’s death, Qahhor began to doubt the utility of the Soviet Uzbek Writers’ Union in securing a future for himself. It was through the Writers’ Union that his main rivals, Sharof Rashidov, the later powerful First Secretary of the Uzbek Communist Party under Khrushchev and Brezhnev, and Vladimir Mil’chakov, the editor of the Uzbek Writers’ Union’s Russian-language literary journal Star of the East (Zvezda Vostoka) in the late Stalin period, had denounced his two novels and thwarted the promotion of his allies.[1] In the years following Stalin’s death, Qahhor saw an opportunity to create an alternate forum for writers outside the union. According to his wife, Kibriyo Qahhorova’s memoirs, in 1951, Qahhor rejected the Writers’ Union’s offer to provide him with a house and instead, two years later, the kolkhoz where he had done his research for his second novel, Red Uzbekistan, offered to build him a house just north of Tashkent.[2] Qahhor, I believe, likely rejected the Writers’ Union house and opted for the kolkhoz house to obtain a modicum of freedom from Writers’ Union surveillance. He would need that freedom when, in 1954, he began hosting young writers and colleagues at his new home for literary circles outside the auspices of the Writers’ Union.[3] Just as he had started these meetings, Qahhor began a short-lived stint as head of the Writers’ Union. According to a July 12, 1956, article in the Soviet central newspaper Literary Gazette, Qahhor’s tenure ended in an explosive plenum meeting in 1956 when Rashidov and Mil’chakov accused him of dismantling the Writers’ Union’s youth outreach, to which Qahhor readily admitted. While it was only for two years, Qahhor had managed to sideline Rashidov and Mil’chakov and direct new talent toward himself.

Qahhor’s fame among ordinary Uzbeks and his renown among his students would not reach its pinnacle until the early 1960s with some of his further successes, but the above 1956 plenum meeting is the first time Qahhor supposedly presented himself as a teller of unforgiving truths. While the Literary Gazette report of the plenum meeting suggests Qahhor offered no defense of his actions against the onslaught of his rivals, Ozod Sharafiddinov, Qahhor’s most loyal student and his biographer, argues, in an account that is oft repeated in Uzbekistan, though Sharafiddinov seems to be the primary source, that Qahhor went on the offensive.[4] Qahhor, he writes, was the main cause of scandal on that July day because he declared, to much fanfare and applause, that Mil’chakov was “the butcher of Uzbek literature,” a reference to Mil’chakov’s role in Stalin’s various purges of writers.[5] Qahhor, Sharafiddinov adds, was reprimanded for this and removed from his position, but the moment also vindicated him because Mil’chakov a few years later left his position to return to his hometown outside Orel in the RSFSR.[6]

Whether Qahhor so brazenly denounced his rival at this plenum meeting or not, Sharafiddinov’s account speaks to the myth Qahhor, and his students, sought to create for himself beginning in the mid-1950s. Qahhor, they had begun to argue with the Mil’chakov encounter, is a writer of conscience who gives voice to harsh and uncomfortable truths, to things that most suspect to be true but are not brave enough to speak of them for fear of offending sensibility or the powers that be. Yet, Qahhor and his admirers declare, he must tell these truths as a vigilant member of the Party and an ideal communist.

This is the picture of himself that Qahhor presents in his literary autobiography, Tales from the Past. In the novella, the foreword and first chapter of which are presented in my translation below, Qahhor endeavors to show the ignorance and cruelty of pre-revolutionary sedentary Central Asia. In each of the chapters, his family is punished and often banished from the conservative community for their unconsciously progressive ideas, such as the use of a bicycle. The family’s frequent banishment makes them “foreigners” (kelgindi) wherever they go, and as a foreigner, Qahhor is the perfect outsider observer. His novella paints him as a great truth teller because in several of the chapters, underneath the community’s easily observable corruption and backwardness often lies yet another stratum of debauchery that only the perspicacious author can uncover.

[1] For more on the denunciation of Qahhor’s first novel, Mirage, see Ozod Sharafiddinov, Abdulla Qahhor (Toshkent: Yosh gvardiya, 1988), 53–60; Christopher James Fort, “Inhabiting Socialist Realism: Soviet Literature from the Edge of Empire” (PhD diss., Ann Arbor, MI, University of Michigan, 2019), 137–45. For the denunciation of The Lanterns of Qo‘shchinor and Rashidov’s role in it, see Sharafiddinov, Abdulla Qahhor, 167–77. For more on Mil’chakov’s denunciations, see Naim Karimov, Maqsud Shayxzoda: Ma’rifiy-biografik roman (Toshkent: Sharq, 2009), 153–211; Naim Karimov, Oybek va Zarifa: Muhabbat va sadoqat dostoni (Toshkent: Yangi asr avlodi, 2005), 119.

[2] Kibriyo Qahhorova, Chorak asr hamnafas (O’zbekiston xalq yozuvchisi Abdulla Qahhor haqida xotiralar) (Toshkent: Yosh gvardiya, 1987), 47–48.

[3] Qahhorova, 38–39.

[4] For Sharafiddinov’s account, see Ozod Sharafiddinov, “Bir nutq tarixi,” in Sardaftar sahifalari (Toshkent: Yozuvchi nashriyoti, 1999), 59–71. Most other sources seem to repeat Sharafiddinov’s account because, while Sharafiddinov was a direct eye witness—the above Literary Gazette article names him as a participant in the plenum meeting—other authors of this account do not appear to have been present. See, for instance, Sharif Yusupov, “Ajib bir iltifot,” in Adabiyotimiz faxri (Toshkent: O’zbekiston, 2007), 60–70; Shodmon Otabek, Do’rmon hangomalari (Toshkent: Sharq, 2016), 39; Ibrohim Haqqul, “Abdulla Qahhor jasorati,” Tafakkur, no. 2 (2004): 28–47.

[5] Sharafiddinov, “Bir nutq tarixi,” 66.

[6] Sharafiddinov, 71.

Tales from the Past

I dedicate this to the fiftieth anniversary of the October revolution.

It swells and moans, that melody,

The “Munojot” sings of unfading pain.

If melody can contain centuries,

What singer can bear those boundless refrains?

-Abdulla Oripov

My childhood years were spent in villages of the Ferghana valley: Yaypan, Nursuq, Qudash, Buvaydi, Tolliq, Olqor, Yug’unzor, and Oqqo’rg’on. In the mid-1930s as I reminisced about that time, I began to see it all as if it were some long-forgotten dream: like the tale of a shooting star disappearing beyond the horizon. A mounted policeman shot a boy named Babar (probably Bobir now) with his rifle, but he didn’t die. The policeman turned to the people and said, “dear Lord, I’ve seen some terrible thieves in my time, but this one had his scalp scraped by a bullet and he didn’t even blink!”

Such memories rise to my consciousness immediately, but countless others remain sunken in the depths of my mind as if tied down by stones. Only Anton Pavlovich Chekhov has taught me the skills to access them.

Thirty years ago, I read every volume of the great author’s twenty-two volume collected works voraciously, never putting the books down. Still a young man, I fancied, as I read, that Chekhov would hand me his famed glasses, the pince-nez ubiquitously on his nose in all his photos: “Here, put these on and look into the past of your people!” he would say.

And that’s what I did. I saw Anton Pavlovich’s “malefactor,” the man who removed the bolts from the train tracks, and my incorrigible thief, Babar, who didn’t even blink when the policeman’s bullet whizzed over his head. I saw that they were two halves of the same apple.

With those glasses, all the memories that had sunk deep into my mind suddenly sprung to consciousness, and the past lives of my people came appeared before my eyes. This is how those tales of the mid-1930s for which I’m remembered—“Thief,” “The Park,” “Invalid,” “Pomegranate,” “Nationalists,”—took form. Though many readers then greeted these stories warmly and though they continue to be published, young readers often object to them now. They tell me that the events and characters depicted in these stories are exaggerations or outright lies.

As the years have passed, the critics of this new generation have become harsher: “Could it really be that no one felt remorse for a man whose ox was stolen? Bureaucrats are people too; can they not empathize?” “Could a person really be a stranger in his own land, can he really not enter a park in his own city?” “Could they really not find medicine for an invalid other than prayers?” “Could a healthy man really not find two pomegranates for his pregnant wife?” “Could an intellectual really be baser than a dog?!”

Recently these critics’ reproaches have reached a fever pitch.

In 1960, I wrote the short story “Terror” about the treatment of Uzbek women in the past. That I would put eight women in the harem of Olimbek dodxoh so offended one woman that she wrote the following lines in an anonymous letter to me:

“Perhaps the past was like that, but now what need is there to revive these horrible pages of history? You seem to give yourself over to fabrication when you look into the past…”

Hearing these reproaches, I did not turn to “fabrication” but picked up my pen and wrote down what I had seen with my own eyes, what I had experienced, and what I remembered. And one of our more famous critics, who read excerpts from the present volume in newspapers and journals, was touched to the quick: “this is terrifying! You’ll poison readers with these images!” The critic himself was born in 1930, and those younger than him will be harsher still, I know. I was going to call this book Moments from the Past, but very well, to satisfy these skeptical and fearful hearts, I have decided to call it Tales from the Past.

The Virtue of Disaster

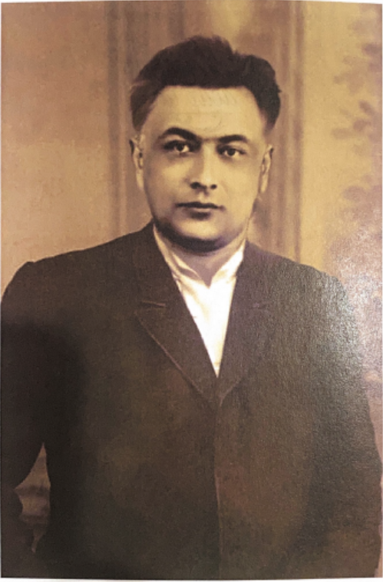

Front row from left to right: G‘afur G‘ulom, Abdulla Qahhor, Kibriyo Qahhorova, Konstantin Simonov

In Yaypan we shared the home of the baker Olim-buva.

In his narrow courtyard of his tashqari, my mother sowed and planted aster, gagea, basil, and savory. The garden, enclosed by the mud walls of the courtyard, reminded of a swallow’s nest. A little door separated the house from the courtyard and the windows of the house were covered with oiled paper to prevent the wayward glances of nomahram passersby. This left the inside of the house so dark that those inside could only guess at the identity of one another.

The courtyard of Olim-buva’s ichkari was also small and covered in vines, the thickness of which trapped the heat in the summer. Day and night his wife noisily span thread on her spinning wheel. She slipped into our end of the house often to speak with my mother. She probably pitied our peripatetic lives, that we didn’t have a home of our own. Sometimes her lungs would fill and she would join my mother in a song of commiseration:

Who has never wandered,

Who has never settled;

Having entered a foreign land,

Who has never been a stranger?

Olim-buva’s son was a servant in someone else’s home and his daughter had long since been married off. He got up in the mornings, often before dawn, to bake bread. When he finished, he put the fresh loaves on the counter in front of his store and left for the city garden, often not returning until late. When he came back, he would count the remaining loaves and the money the buyers had left him. If there was less money than bread, he would grumble but not because he regretted the loss, but rather because he regretted that the person who had taken it without paying would burn in hell.

The hot days of summer. Because our little house was dark, it was often cooler and full of flies. One day my father closed the doors and shutters of the house tightly. He began to smoke some peppers inside to kill off the flies. The smoke was so piquant that my father barely made it out alive. He coughed and hacked for a good while afterwards. Having heard what he was doing, Olim-buva became upset.

“Hey smith, don’t torture God’s poor creatures: God made the flies too, he gave them life!” he shouted over the wall.

My father immediately put out the fire.

One day my father’s nephew, a hunter, visited us. While hunting in Pastqo’riq, he had run out of bullets and asked my father to make a few for him. Despite my mother’s warnings, I was fascinated by the explosive power of those little things. Our guest lit some gunpowder for me. Later he opened a percussion cap, showed me the red on top and the white inside, and then he exploded it by smashing it against a rock. Hearing that crack, I jumped from fright, but quickly began hopping in excitement. When he wasn’t looking, I stole two caps from his bag and hid them in my felt boots. After he had left, I’m not sure what I was thinking, I trapped a fly between the two caps on top of the little anvil and then brought my hammer down on them with all my strength. The caps exploded with an ear-ringing boom. My mother, who was planting basil in the garden, screamed and dove into her young sprouts for safety. Olim-buva’s wife dove on top of her but then, realizing what had happened, looked at me with wrath in her eyes: “What have you done?! Go, tell your father!” she barked. My mother was still yelling hysterically in her basil, “put on your shoes!” I was frightened, so I put them on and ran out. Our shop was in the city center, and the sound of the explosion had carried there. My father had been working on the bellows, but when he saw me, he began hurriedly asking about my mother. I managed only, “she’s crying.” My father took off his apron and mounted his “devil cart” to head home. Still shocked, I sat down. On the other side of the crossroads, the warbling of the quails in their cages and humming of partridges in stores gave no peace. I left the store and was approaching one of the partridges when I heard my father calling. My father got off his “devil cart” yelling: “you shot at your mother! Can a person really shoot at his mother who will give him a brother?!” He handed me the rope to the bellows. I understood from his sudden change in mood that my mother was all right, and I began to pull the rope.

My father removed a red-hot piece of iron from the forge and began to strike it on the anvil. A bean-shaped piece broke off and rolled into my boot, which I had put on the wrong foot. The hot metal stuck to my foot, and I screamed in pain. My father ripped the boot off, and laid me down on the bench in the store. When I came to, there were five or six people over my head looking at me. One wrapped me in a towel while another blew on my wound. A third exclaimed: “what a strong boy! He’s not even crying. Strong as an ox, this one.” It’s true, I didn’t make a sound, but my body was shaking so that tears came to my eyes. One of the men wrapped felt around my wound and tied it with a thin cloth. Others brought candy and sweets. After things had calmed down, my father turned to me and smiled: “everyone who calls himself suffers and burns towards that end!”

Towards evening, my father closed the shop and carried me home.

When my mother heard about my burn, she fainted. Later she cursed herself for sending me to the shop alone. My mother, who had laid eight children, born before and after me, in the ground, had never trusted me to take care of myself. She never let me take a single step outside the gaze of her vigilant eyes. My mother was beside herself now, having completely forgotten that I scared her half to death earlier that day. Both she and my father for hours questioned how I managed to get to the store alone. It was as if every misfortune awaited me on my path there, and somehow, thanks to my deftness, I arrived at the shop unharmed.

Just then I grew up in the eyes of my parents—a thousand times praise God—and they released me from their supervision. I was now allowed to go out on the street, but I never returned with the happiness that their sudden support promised. The next time I went out, I fell in the ditch in front of our door: a corn stalk lay across the small bridge over the ditch, and when I went to kick it in, I slipped and fell in myself. Someone helped me up, and I ran back inside crying. My mother, her heart about to burst, sprinkled water on my face, and without taking my wet shirt off, she lit a cloth and circled my head with it while chanting. After that, my mother didn’t allow me to go out for the next week. Another day I was sitting in front of our door, playing with clay, when a group of Cossacks rode in from the village center. I had never seen a Cossack. Engrossed in the sight of their blue caps with red bands and their forelocks peeking out from underneath, I started after them. When I finally looked away, I was in a field. I turned back, but I couldn’t find our street. I began crying, but fortunately, a cart appeared. The driver stopped, jumped down, and began to talk to me. It turned out he knew my father. He set me on his cart and took me home. I never told my mother about what happened because she surely would have locked me up even longer. But the cart driver told my father, and when my mother heard, she fell into a panic.

“Oh, my child, God alone saved you! If one of those Cossacks had grabbed you by the leg and knocked your head against the ground, or taken you with them? Remember: if you see a Cossack, run, and if you can’t run, throw yourself in a ditch!”

My father, to the contrary, praised me.

“Great job, great, you’ll be a brave man someday,” he said and turned to my mother, “the brave ones always run towards the Cossacks!”

From that point on, my father overruled my mother and gave me my independence. I was allowed to leave and go down whatever streets and alleys I desired, play with the children on the street, and I did this all without getting hurt or lost.

Ramadan had come. The soft playing of distant drums, the horns sounding like the bleating of goats woke everyone in the morning. Judging by my parents’ words and their behavior, the fast was a great thing, worth getting up early with them every morning. But the mornings weren’t as interesting as the evening bazaars. Early in the month, my father took me to one.

At the village center, the countless shops had at least two, sometimes three candles lit. The street was full of people. Yelling, screaming, laughter, song. The salespeople shouted: “Hot bread here!” “Get your samosa here!” “Candy!” Children ran around with sparklers, spraying sparks everywhere. From behind the trees, I could see the tails of fireworks that created new constellations in the sky. Their sparks would flame up and die out while the largest one would dive back to earth.

On another night, my father brought me to the samovar at one of the teahouses. There was a crowd of men there, all laughing. A large lamp in the center of the teahouse illuminated the platforms where the patrons were lying and chatting. My father led me between those platforms until we arrived at one where the men there made room for us. From which side of the platform, I couldn’t tell, came a thin, yet powerful voice singing a song. I looked around furtively until my father pointed to horn so large that no one could take it in their embrace. As I looked at it, I noticed that the song came from inside the horn that was attached to a yellow box. I had heard of this “song-machine” before, but I had never seen one. I stared at it intently. When the song ended, a new voice replaced the old: “thank you, Hamroqul-qori!” I couldn’t figure it out. There must have been some little mustachioed men imprisoned in that yellow box.

Then came a loud cracking noise. “Don’t be afraid, don’t be afraid,” my father repeated, “it’s just a rocket.” I looked over to see something like a frog leap into the air with a crack. No one in our circle jumped like I did. Instead, they all laughed. A bearded man steered the conversation to an event in Xo’jand. There was, he started, a famous rocketeer in Xo’jand who once, when invited to perform for a rich man’s wedding, tied four rockets to his waist and launched himself above the trees. Luckily, the partygoers had tied a rope around his leg and pulled him down. Our circle was rolling from laughter.

The “song-machine” started to play again. Another rocket launched, spraying smoke and sparks everywhere. Then our table started playing Buvaqovoq.

A small man with a Kyrgyz-looking face entered from behind the reed mat that served as a door and placed three leather bags on our platform, all the while advertising the fermented horse milk inside them. From behind that same mat emerged a tall man with a big gut and a beard parted in two. He rode a white donkey. That was Buvaqovoq. Buvaqovoq came towards the Kyrgyz and began asking about the beverage. The Kyrgyz, without skipping a beat, told him two coins for one cup. Buvaqovoq countered: ten cups for one coin. The Kyrgyz man said nothing, obviously furious. The men around chuckled. Buvaqovoq got off his donkey and tasted the drink from one of the bags. Then he opened the second and tasted that one. As the Kyrgyz closed the two bags tightly to prevent them from leaking, Buvaqovoq took the third one and poured himself cup after cup. With every cup he downed, he cried, “my only offer – ten cups for one coin!” The Kyrgyz yelled and cursed, but he couldn’t leave the other two bags. The crowd was holding its sides in laughter.

Thanks to the misfortune of the percussion cap, I was now grown. I went to night bazaars and left the house during the day whenever I wanted. I played whatever games there were with the local children, and my mother didn’t ask questions. On the contrary, she was happy for me. But just when I had made a few friends from among those children from whom I was estranged, we had to leave the neighborhood.

One day my father mounted his “devil cart” and left for Kokand. When he returned later than evening, he came across Olim-buva’s sister, a woman in her eighties. My father didn’t ring the bell, startling her as he quickly passed by. Frightened by the sudden gust of wind, the old woman lifted her head. When she saw that man-shaped monster with legs that didn’t touch the ground fly off, she fainted. People gathered around her unconscious body. Baffled, they eventually decided to take her home, loading her into a wheelbarrow. My father, realizing what had happened, didn’t leave the house out of fear. He didn’t even go to the shop. Three days later the old woman died. Afraid of Olim-buva and the rumors, my father rapidly lost weight. My mother couldn’t lift her head, so heavy were her tears. A week after her death, Olim-buva sent a messenger to my father: “Fine, you need not fear, my sister’s time had come, it’s God’s will. But don’t ride that “devil cart” again. Ever since you brought it here, things in Yaypan have taken a turn.”

The next day my father took the “devil cart” to Kokand and sold it. Then he met with Olim-buva and gave him two hoes and an axe to atone for his sins. But Olim-buva paid him for them, despite my father’s protests.

With that everyone calmed down, but the peace was not to last. Within a week, another disaster took place.

As my father left for his shop in the morning, he saw a woman with a large camel’s thorn stuck in the back of her paranji. My father caught up with her and stomped on the thorn. He extricated the thorn, but the woman, feeling a tug at her paranji, snapped back and stared at my father before hurrying off. This woman turned out to be Olim-buva’s married daughter. When she arrived home, she told her father that the smith had attempted to unveil her in the street.

The next day Olim-buva woke up the entire neighborhood.

“Hey, devil cart! Hey, foreigner! Come out here! Come out here, I said!”

We had never heard him produce such loud sounds. My father looked at my mother terrified. Her face had gone pale. My father ran out to the street. I started out too. I had never seen Olim-buva like that. Where was the old man who always had a smile, who always talked so sweetly? Before us was a terrifying visage, eyes bulging from their sockets, face paler than his white beard, his entire body shaking. When he saw my father, no words, only curses emerged from his mouth. He spat what his daughter had told him at my father, cursing my father as a “foreigner dog!” My father only bent his head.

“Elder, just listen,” he started, but the old man was already coming towards him with his fist raised.

“Pack up your bed and get out of my house, you dog, you stranger!” he screamed. He rushed into our half of the house and, paying no heed to my mother, who had frozen in fear, he entered our house.

My father followed him in, pleading “elder, elder.” Olim-buva exited the house with my father’s sleeping mat and threw it into the street where a crowd had gathered. No one tried to comfort Olim-buva. On the contrary, someone yelled:

“There’s no good that can come from some who rides that devil cart. Beat him!”

Olim-buva lowered his head and walked by my father.

“Did you think my daughter is just some street-walker? What’s that, dog?! If I ever see your face again, I’ll do things so uncivilized that my wife won’t let me back in the house!” he yelled and entered his home.

Everyone in the village heard the commotion.

My father picked up his sleeping mat from the road and brought it back to the house. My mother was beating her head against the wall as she grasped at her hair and wailed. My father explained what had happened with the thorn. He tried to comfort her.

“The old man won’t listen to anyone now. We’ll give him time, and he’ll realize his mistake and be ashamed of himself.”

My mother suddenly stopped crying.

“You should be ashamed. You should be ashamed of making eyes at a married woman!” she yelled.

My father frowned but said nothing. He walked out to the street.

He returned later that night. He told us he had found a place in a neighborhood called Qo’shariq. We loaded our things into the cart he had brought and left for a new home.