by Zilola Khalilova, Tashkent

When looking back at the Soviet past, today most of the scholars of Islam in Uzbekistan express resentment towards the Party state which promoted atheism and constrained religious freedom. But there are some who think differently, and show sympathy for the USSR. How to explain this phenomenon? The answer to this question lies perhaps in the private, indeed recondite space of one’s own personal experience.

While collecting data on the history of Islamic education in Uzbekistan under Soviet rule, I had the good fortune to interview Abduqahhor G’afforov (also known as Abduqahhor Shoshiy), one of the most prominent scholars of Islam in Tashkent who served the Soviet government in various capacities. During our extended conversations, Shoshiy reflected upon a broad range of issues about Soviet Muslimness, speaking inter alia about how Soviet citizens who fashioned themselves as “Muslims” positioned themselves vis-à-vis atheism and secularist policies. Unlike many other interviewees, Shoshiy impressed me for his conciliatory attitude towards the USSR; and this took me rather aback, for he faced imprisonment, though short, during the perestroika for publishing a religious text without the sanction of the state. In fact, Shoshiy was adamant about one thing: he had managed to build a successful career by seizing the opportunities afforded to him by the Soviet regime. Equally, he has regarded himself as a proponent of what he has termed “genuine Islam”, an Islam, that is, untarnished by the influence of Soviet atheist culture. But how could one feel sympathy for his Soviet patria, and claim a pedigree of a spotless religious man? To answer this question requires that one anatomize how Shoshiy navigated through the Soviet era. Starting from his time in a madrasa and continuing through his roles as a director, rector, and in a leading role in the Muslim Spiritual Board of Central Asia (SADUM), he faced the challenge of maintaining his religious identity while also aligning himself as a faithful Soviet citizen. Such a Janus-faced commitment served as the foundation for his prosperous career, rooted in his contributions to the state.

The intellectual journey that led Abduqahhor Shoshiy to become a scholar of Islam does not differ significantly from the biographies of other Uzbek ulama. Born in 1939 in the old town of Tashkent, Hasti Imom mahallah, Shoshiy received a private religious education by a mullah. He apprenticed under a certain Domlo Hoshim, who taught him Arabic and how to read the Qur’an. Between 1951 and 1954, Domlo Hoshim led a hujjra (an underground Islamic teaching circle) at his home in the Yovdiya neighborhood of the Oktyabr (current Shayhontohur) district of Tashkent. “After just a month of training,” Shoshiy claims, “I was able to recite the Qur'an in its entirety.” Over time, he learned the Arabic script and move on to other texts. He studied the rules of tajwid under Fakhriddin Qori Aka, who resided in the Halim Kop mahalla and worked as a typist in a printing house in the Chorsu district. Endowed with this privileged knowledge, Shoshiy could apply for madrasa education. This is why we find him in Bukhara at the distinguished Miri Arab madrasa between 1956 and 1961.

At that time the Miri Arab offered tuition to only about 50 students. And when questioned about their post-graduation plans, most of Shoshiy’s peers explained that their intention was to be employed as an imam at a mosque. But Shoshiy scoffed at them: to become imam was relatively easy and did not require any deep knowledge of the Islamic sciences. It was enough to be able to read prayers during marriages and funerals, and master the rules of worship! And if one had a pleasant voice when reciting Qur’anic verses, that could guarantee a comfortable life. Shoshiy was different, however: he never aspired to become an imam. All he wanted was to become a scholar (Uzb. olim), and to be considered a member of the Soviet ulama!

Shoshiy’s journey did not stop at the madrasa. In 1962 he enrolled at the Tashkent State University, where he majored in law, a turn which was made possibly most probably by his affiliation with the Communist Party. Only a party card could afford access certain educational opportunities. After only a year he changed tack: in 1963-1964, Shoshiy joined the Institute of Language and Literature, where he worked as an Arabic translator. He was part of a group, under the leadership of the acclaimed Uzbek scholar Hamid Sulaymonov, focused on studying the works of Alisher Nava’i. During his tenure at the Institute of Language and Literature, yet another local academic, the famous Yahyo G’ulomov, invited him to collaborate on the Uzbek translation of Tabari’s chronicle. However, not even half a year had passed when Shoshiy was forced to leave academia to avoid any potential complications for his employers, which may have arisen given his madrasa background.

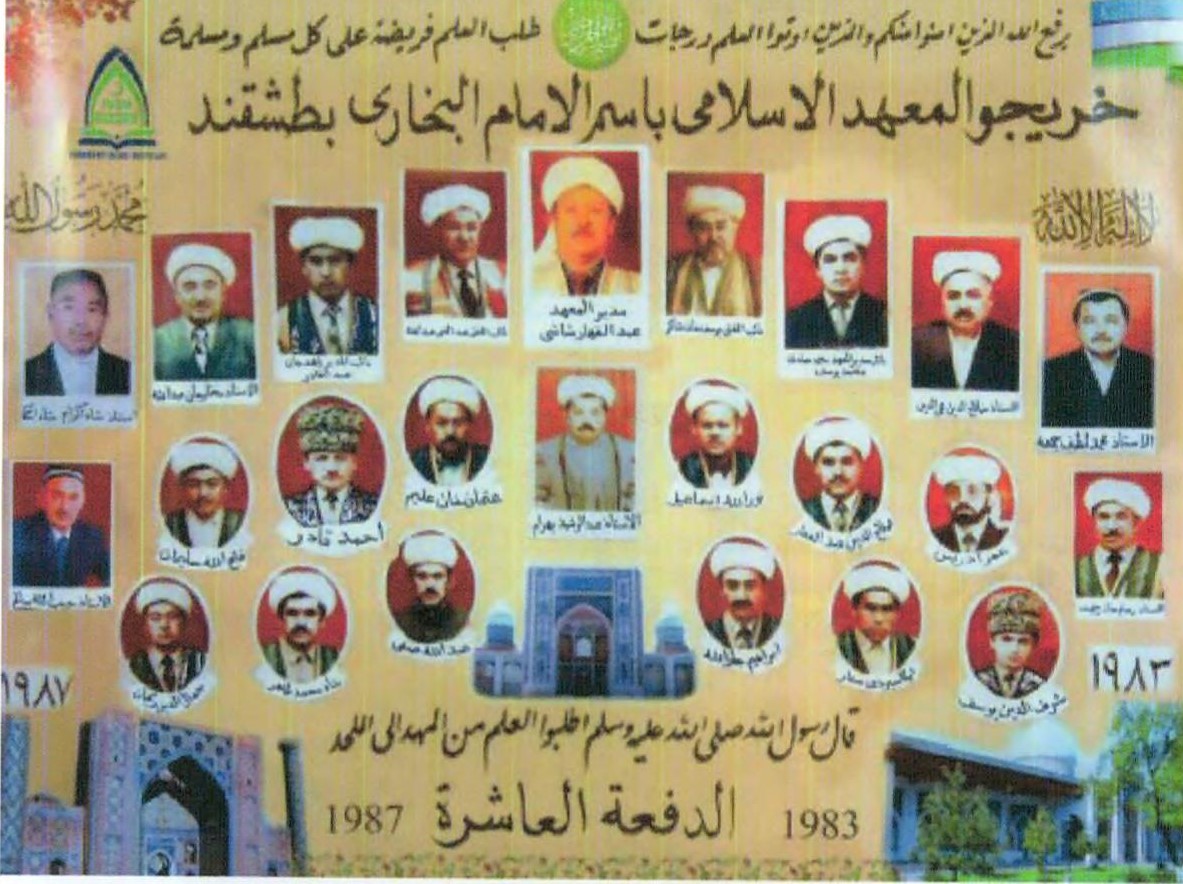

Shoshiy was no doubt extremely resourceful, and we find him between 1966 and 1969 in Egypt, at the prestigious al-Azhar University, where he spent three years as an auditing student. His experience in Cairo gave a boost to his career. In the early 1970s, he secured the position of director at the Miri Arab Madrasa in Bukhara. His flamboyant style, however, seems to have attracted the ire of many people, and soon thereafter he was demoted to the role of ordinary teacher. During our conversation he explained that had he refused to step down from the office of director, he would have been required to pay the state for the expenses incurred for his education in Cairo. His patience proved rewarding: From 1970 to 1979, he was appointed as the Head of SADUM’s foreign relations department, and in 1984 he began to serve as rector of the Tashkent Islamic Institute (Oliy Mahad).

Things took a different, unfortunate turn at the end of the 1980s. Most probably in bad odor with other members of SADUM’s hierarchy, he was first removed from his position and soon thereafter imprisoned under the pretext of permitting the publishing of the Haftyak, a primer to teach the Qur’an. That was not the end of our protagonist’s story, though. In the following years, Shoshiy managed to restore his renommée. From 1988 to 1992, he served as a staff member in the Muslim Spiritual Administration of the North Caucasus in Buinaksk.

With the fall of the USSR, he repurposed himself as director at the educational center Ilm (Uzb. “Knowledge”), where he focused on teaching Arabic and Chaghatay. It was during these years that Shoshiy’s long sought-for aspirations for scholarly activity seem to have come to fruition: he published several texts in Uzbek translation, such as Imam Abu Bakr Qaffal Shoshiy’s Jawami’ al-Kalim and Hakim al-Termizi’s Manozil al-Ibad. He furthermore authored a series of works on Islamic dogmatics and rituals such as Islom Aqidasi, Islom Arkonlari, Namoznoma, Ro‘zanoma, Hajnoma, Zakotnoma, Miftah al-qira’a, and Qur’oniy hikoyalar.

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to argue that one of the most salient challenges for the students of Soviet Islam is to comprehend how the Muslims of the time shaped their identities and how they regarded themselves vis-à-vis broader political and societal processes. Indeed, certain individuals might have primarily identified themselves as devout believers, placing their religious identity above any political affiliations. Particularly those who pursued scholarly or clerical roles, such as imams, focused, that is, mainly on the service to their parishes. Others, suchlike Shoshy often found themselves treading a more delicate path, attempting to balance their commitment to communism with their ambitions as scholars of Islam.

Time and again, Shoshiy clarified to me that he did not feel any hostility towards the Soviet state. In fact, he dutifully contributed to its development and consequently rose to prominent positions, he himself argued. Simultaneously, Shoshiy maximized the opportunities afforded to him, particularly in terms of education. He pursued his studies abroad in the Middle East, delved into Arabic and other foreign languages, and harnessed his knowledge to enhance educational standards during his tenure as a director.

And yet to say more about who Shoshiy was remains in the end an insurmountable task. Those who completed education at the madrasa typically engaged in mosque-related activities and prayer. At the same time, a significant number of ulama who made it to the leadership of SADUM had muddied their feet with the KGB or held degrees from state universities. Shoshiy, however, emerged from a religious background, underwent religious schooling, and possessed a profound understanding of religious matters – but neverthless remained faithfully dedicated to serving the state. A scholar apparatchik?