June 1, 2018 | Stefan Donecker | HI Research Blog

Origins of a German Master Narrative, 1500–1830

“Ancient is the German’s urge to wander; presumably it led him from the Orient to settle by the six rivers of Germany, and made him see the glory of Rome beyond the Alps. The migrations of the Cimbri, the speeches of Ariovistus and the words of Hengist, as recorded by Bede, all bear witness to it. It is the only explanation for the Romans’ fear, for their feeble attempts to repel the mighty German nation, and for the Germans’ eventual inundation that swept to Britain, over the Alps and Pyrenees and all the way to the Atlas range.” Friedrich Ludwig Jahn, the legendary “Turnvater” and one of the key figures in the early German national movement, did not hide his enthusiasm for migrating Germanic tribes when he published these lines in 1810 in his book Deutsches Volksthum. His praise is one of the earliest expressions of an interpretation of history that soon became commonplace in German national romanticism: the narrative of the “Germanic Völkerwanderung”.

The word itself is almost impossible to translate: “Völkerwanderung”, literally “the wandering of peoples”, refers to the migration movements of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages, between the late fourth and the mid-sixth century AD. But while the English and French designations for this migration period, “barbarian invasions” resp. “invasions barbares”, had pronouncedly negative connotations and were associated with wanton destruction by plundering hordes, the tale of the “Völkerwanderung” was, above all, a tale of patriotic pride: Allegedly Germanic tribes like the Goths, the Vandals and countless others had roamed Europe in far-reaching campaigns of conquest, brought the mighty Roman Empire to its knees and founded their own kingdoms in its stead. The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries indulged in tales of martial prowess, pioneer spirit and indomitable Germanic virtue, which modern Germans supposedly shared with their barbarian ancestors.

During the last decades, historical studies on the transition era between late antiquity and the early Middle Ages have thoroughly refuted the historicity of such images. The Historical Identities group at the Institute for Medieval Research has, in fact, spearheaded several research initiatives that contributed to a rethinking of traditional narratives, dispelling the myth of an ingrained antagonism between the Roman Empire and the barbarians beyond the limes as well as stressing the continuities between the ancient and the medieval era. The Roman world was transformed rather than destroyed.

However, the time-honed narrative of the “Völkerwanderung” proves persistent, especially in popular historiography, and has even gained new prominence during the last years – albeit with a somewhat ironical twist: Since the beginning of the so-called European migrant crisis in 2015, political commentators have appropriated the “Völkerwanderung” motif and employed it as a warning example: The Roman Empire was allegedly destroyed by waves of migrants with a penchant for violence and an unwillingness to integrate into the host culture – and the European Union is supposedly going to share the same fate. The very same Germanic tribes that had once been glorified and idealized by German nationalists now embody the distorted image of the destructive migrant.

Both the traditional positive and the recent negative depictions of the “Völkerwanderung” and its barbarian protagonists are at odds with the historical reality of the fourth to sixth century AD. Readers wishing to explore the contrast between historical facts and political instrumentalisation of this period are advised to consult the literature listed in the “Further Reading” column to the right. In the following, I intend to pursue another line of inquiry that leads five hundred years into the past. To truly understand the “Völkerwanderung” motif that still appeals so strongly to the historical imagination, it is necessary to examine its origins – origins that can be traced to the heyday of German humanism in the years around 1500.

The only surviving manuscript of the ethnographical treatise De origine et situ Germanorum, written by the Roman historian Tacitus around 100 AD and commonly known under the shortened title Germania, was rediscovered by Italian scholars in the 1450s. It took almost fifty years for the text to reach Germany, where it was enthusiastically received among German humanists. They quickly asserted that the contemporary “Teutsche” were descendants and heirs of the ancient Germani described by Tacitus. If we were to choose the one single line from Tacitus’ writings that had the strongest influence on the imagination of the Germanic among humanist intellectuals, a few words from chapter II of the Germania would be a strong contender: Ipsos Germanos indigenas crediderim. – “The Germani themselves I should regard as indigenous”.

This succinct statement triggered the “Tacitean paradigm shift”, a fundamental reimagining of the Germanic past that emphasised autochthony and uncompromising territoriality as indicators of Germanic virtue and pre-eminence. The leading scholars among the first generation of German humanists, in the early sixteenth century, were, of course, aware of the migrations of the Goths and the other barbarians that had been documented in ancient sources – but they did not consider them particularly important. A proper Germanic tribesman was, after all, supposed to remain in his native land, as Tacitus had testified.

Credit for the reintroduction of Germanic mobility into humanist discourse goes to the Viennese historiographer Wolfgang Lazius. In his 1557 treatise De gentium aliquot migrationibus (“On the Migrations of Certain Tribes”), Lazius coined the term migratio gentium, the Latin equivalent of “Völkerwanderung”. He has often been labelled as the “inventor” of the “Völkerwanderung”, although such an appraisal is actually misleading. Lazius never used migratio gentium as the designation of a particular historical period, nor did he perceive it as a chain of events, as the later term “Völkerwanderung” implied. To him, spatial mobility was a typical trait of ancient barbarians that characterised their behaviour throughout history, and must not be relegated to a particular “Völkerwanderungszeit”. Lazius did manage to remind his humanist colleagues of the importance of the barbarian migrations that had previously been marginalised under the influence of Tacitus’ Germania. Several smaller tracts on Germanic migrations published in the latter parts of the sixteenth century indicate that Lazius’ efforts indeed had a strong impact on the scholarly community.

In the seventeenth century, however, the academic pendulum swung back in the opposite direction. Philipp Clüver’s Germania antiqua, published in 1616, set the standards for scholarly inquiries into Germanic antiquity and became the main authoritative textbook on the subject. Clüver did neither doubt nor dismiss the mobility of ancient barbarians that Lazius had stressed. But as a pioneer of historical cartography, Clüver relied strongly on historical maps to disseminate his findings – and these maps did assign a specific area to each Germanic tribe. Involuntarily, Clüver’s usage of static maps fostered a return to a more sedentary, territorial image of Germanic antiquity.

The Era of Enlightenment refreshed the interest in barbarian migrations among the academic Republic of Letters. As Christian periodisations of universal history faded in importance, scholars tried to establish secular alternatives. During the eighteenth century, the “Völkerwanderung” was gradually developed into the defining watershed event that separated Greco-Roman antiquity from the Middle Ages. By the 1790s, as apparent from the writings of Herder and Schiller, the term had gained general acceptance as a period designation.

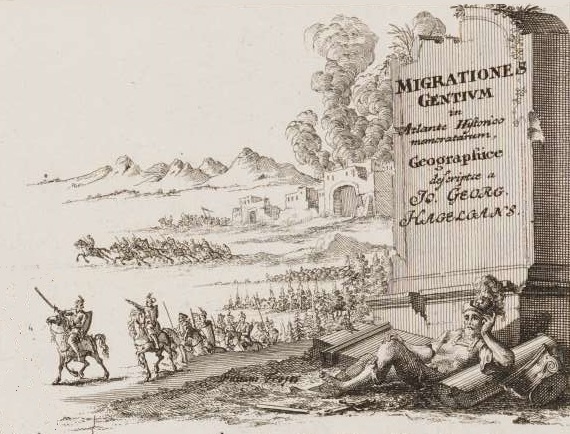

At the same time, eighteenth-century scholars developed the concept of migrationes gentium beyond a purely descriptive approach. Earlier treatises recounted historical migrations and traced the wanderings of particular tribes, but they rarely provided any theoretical and abstract reflections on the nature of barbarian migrations. This changed during the enlightenment, as scholars sought to establish typologies of migration and to integrate the phenomenon of barbarian mobility into their models of societal development. Accompanied by new techniques of knowledge dissemination – the first map of barbarian migrations utilising the now familiar linear arrows was published by Johann Georg Hagelgans in 1718 –, nuanced and subtle interpretations of late antique and early medieval migration processes were proposed. The peak of critical analysis was reached in the 1730s and 1740s in the erudite writings of Johann Ehrenfried Zschackwitz, an undeservedly forgotten jurist and historiographer, who re-examined the ancient accounts of Germanic invasions and questioned the logistics of large-scale migrations. He reached the radical conclusion that “Völkerwanderungen” in the literal sense of the word were simply impossible. The events described by ancient authors, he argued, were merely military campaigns that were later misinterpreted as entire peoples on the move.

Thus, between the sixteenth and the eighteenth century, a gradual shift from a descriptive, event-centred narrative historiography to an increasingly theoretical, model-oriented understanding of barbarian migration can be observed. The rise of modern nationalism, however, caused these analytical achievements to lapse into obscurity. Both the academic and especially the popular historiography of the nineteenth century required a rather straightforward patriotic narrative of the “Völkerwanderung”, as a contribution to the construction and confirmation of German national identity. The enthusiasm for migrating and conquering Germanic ancestors can, in this sense, be interpreted as a counter-reaction to the scepticism of the enlightenment.