May 22, 2023 | Laura Gazzoli | Historical Identity Research Blog

‘The North’ in Europe is a direction that conjures up strong images: mist-enshrouded mountains along a fjord, the midnight sun, legends of ancient gods and heroes. Or your associations may be less positive: particularly if you’ve spent time in Scandinavia, you may also think of expensive food and drink and the grind of months-long cold and darkness.

For medieval authors, ‘North’ could be no less an evocative direction. In the course of working on the project Mapping Medieval Peoples (MMP), I’ve tried to explore and explain what various writers thought about Scandinavia, Iceland and the peoples who lived there through the possibilities offered by the MMP engine and put together a case study on the topic, which I’ve called ‘Mapping Morals’, as many medieval authors used the North as a mirror to reflect the supposed virtues, or vices, of their inhabitants. In this post, I’ll look through some of them – from a writer who, in light of the violence of the viking depredations on Europe in the ninth and tenth centuries, saw the peoples of the north as naturally harsh and violent, through a dyspeptic English exile in Denmark and a cleric in the north of Germany who gathered reports of far-off places, to a Dane who formulated the idea of the northern peoples being the strongest, to a Polish bishop who saw them as effeminate.

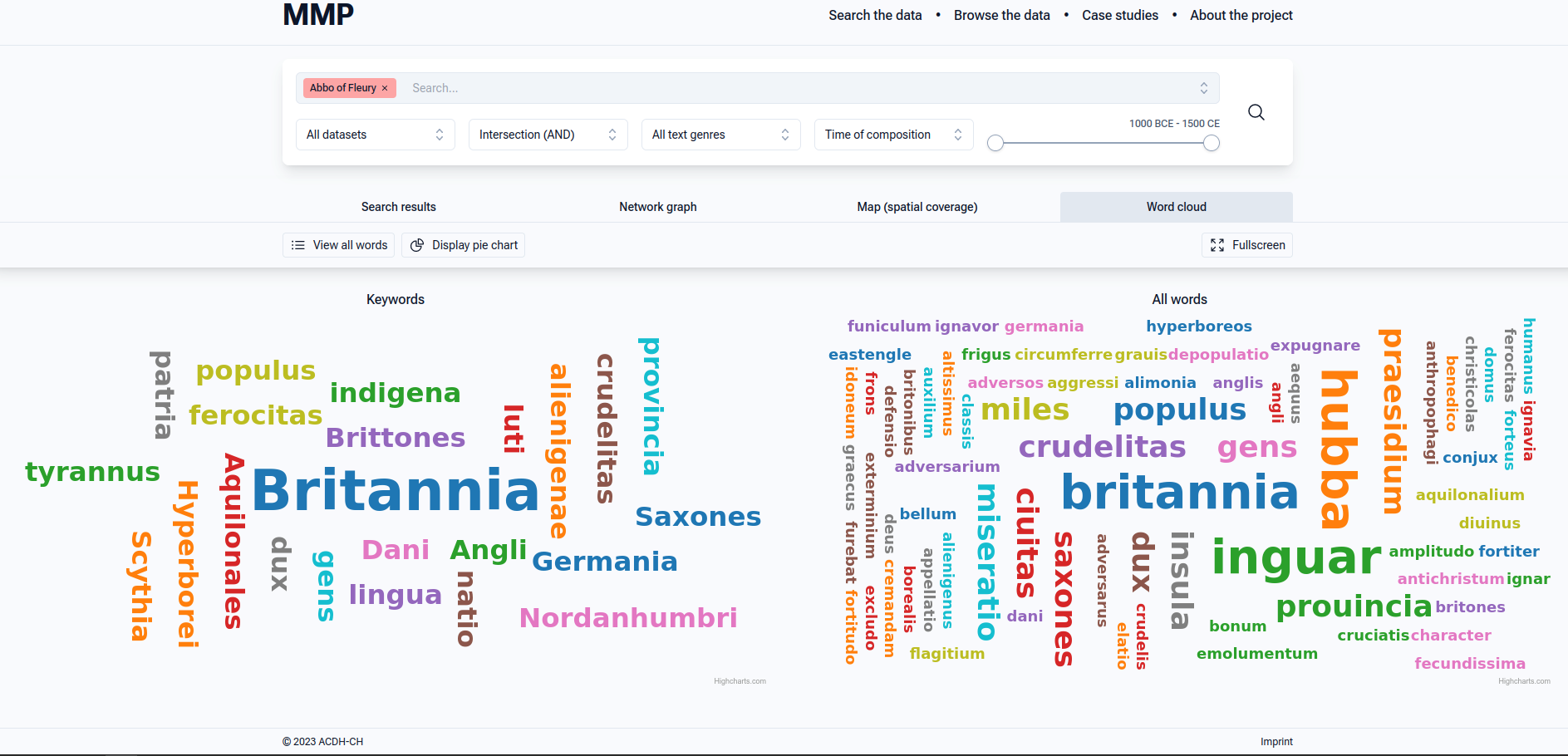

Let’s start with Abbo of Fleury, a French monk who wrote his Passion of St Eadmund while visiting English monastic houses around the end of the tenth century, when Danish attacks on England had begun being a major problem again. Looking back on the previous century’s viking problem, and the death of King Eadmund of East Anglia at the hand of the marauders, provided some context. He saw the north as the place where, according to the Biblical tradition, Satan set up his throne to challenge God, and from which all evil poured forth over the earth (Jeremiah 1:14). The people who lived there had a naturalis ferocitas (natural fierceness) – which made them eat human flesh and persecute Christians. In MMP we can see the keywords (ones we’ve specifically set up in MMP) and words in general (from the full text) Abbo uses in his text visualised in a word-cloud: crudelitas, ferocitas, tyrannus, antichristus (see Fig. 2).

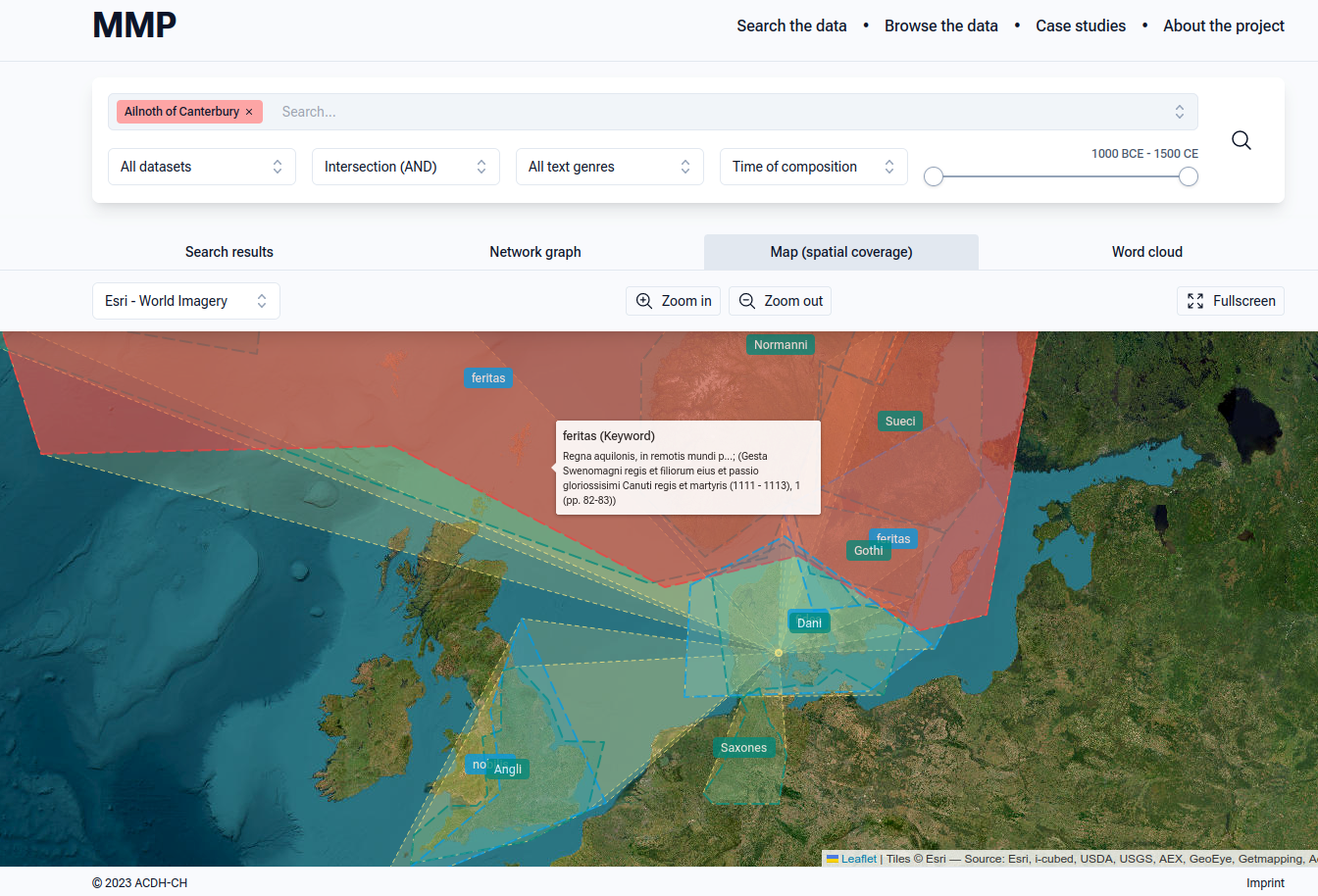

Someone who turned to Abbo in later centuries was Ailnoth of Canterbury – an English cleric, probably a monk, who moved to Denmark probably in the 1080s or 1090s. He also saw the North as a hostile climate for the Christian faith: the Danes, at the southernmost ends of Scandinavia, were the best people there, but he still found time to grumble about how they didn’t observe Christian fast- and feast-days properly, and how they were unwelcoming to foreigners, including foreign clergy such as himself. The rest of the northern peoples – he uses the blanket term Aquilonales – were given to persecuting Christians, whose priests some of them blamed for the infertility of their soil – and this infertility in turn made them harsh, given to wildness (feritas), and again unable to observe the proper rhythms of feast and fast throughout the Christian year. With MMP we can plot Ailnoth’s conceptions of the North onto a map (with ‘cones’ that radiate out from his point of activity, Odense, to the areas he was writing about – see Fig. 3).

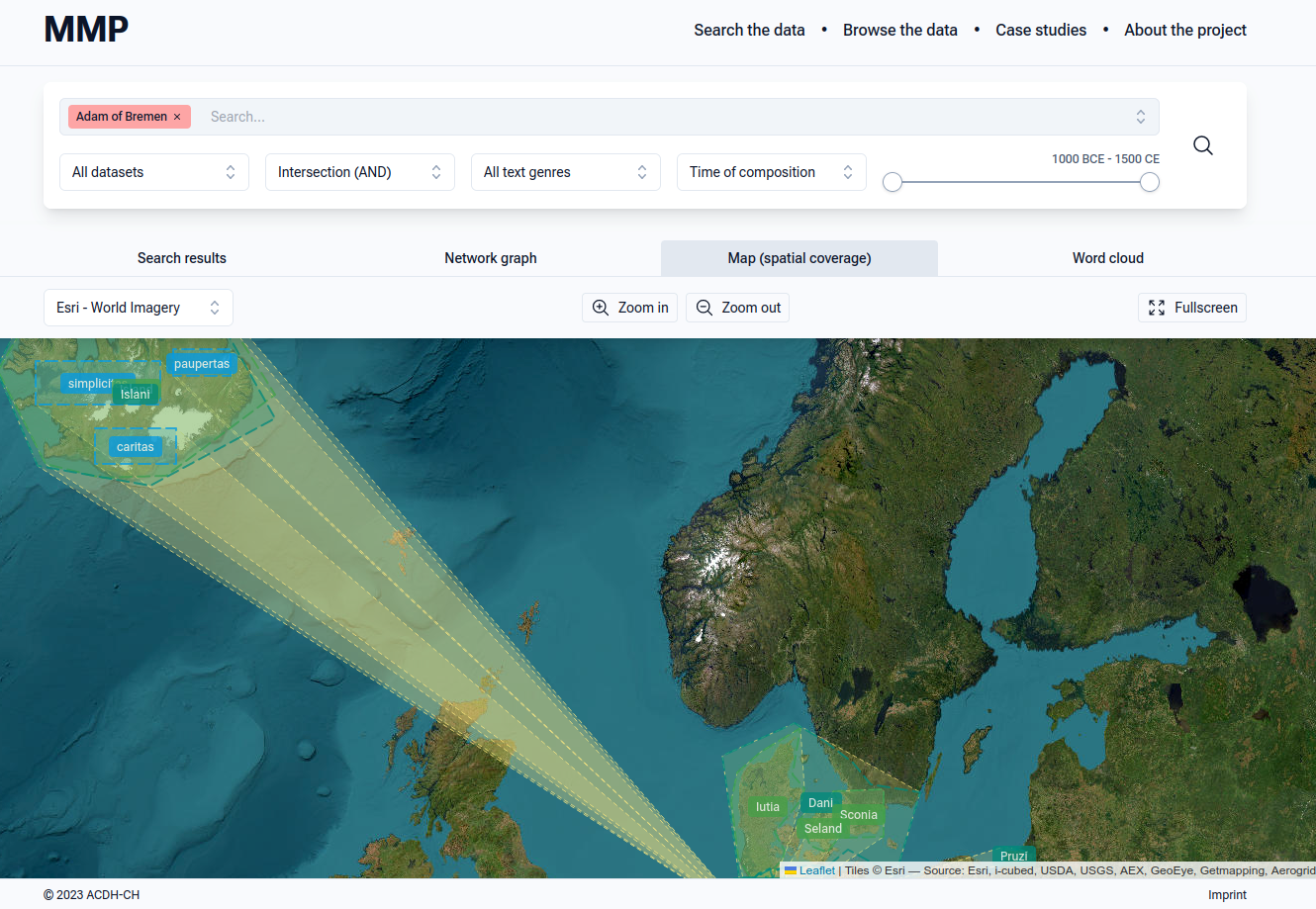

There were differing views on the North, however. Adam of Bremen, a German cleric writing in the 1070s. One of his informants was the Danish king Svend Estridsen (1047-1076) as well as various bishops and missionaries who had been active in Scandinavia. He provides a glowing report of the Christianity of the Icelanders – the extremes of their northern climate do not, like they do for Ailnoth, make them harsh and scarcely able to be proper Christians, but rather, it gives them essential Christian characteristics: poverty, simplicity, and charity (paupertas, simplicitas and caritas) – we can see how MMP can visualise this (Fig. 4).

Adam also says the Icelanders had laws which made them practically natural Christians before they had even converted. His emphasis of the role of the bishop in Iceland suggests that this account is derived from Bishop Ísleifr who came to Bremen to receive consecration in 1056, and his following, and thus, I would argue, may have its roots in an Icelandic self-perception of the eleventh century.

Adam writes:

By the end of the twelfth century, history writing had begun in earnest among Scandinavian and Icelandic authors. In Denmark, Saxo Grammaticus had strong views on the merits of the Scandinavian peoples and those around them: in one passage he blamed the defeat of the legendary Danish King Harald Hildetand by the Swedes (VIII.4.2) by claiming that his army was composed of too few Scandinavians, and too many Saxons, Slavs and other ‘effeminate’ peoples. Saxo in some ways goes back to the view of Scandinavians as harsh and warlike, but makes it into a positive trait, articulating a chauvinist view about the superiority of northerners in battle.

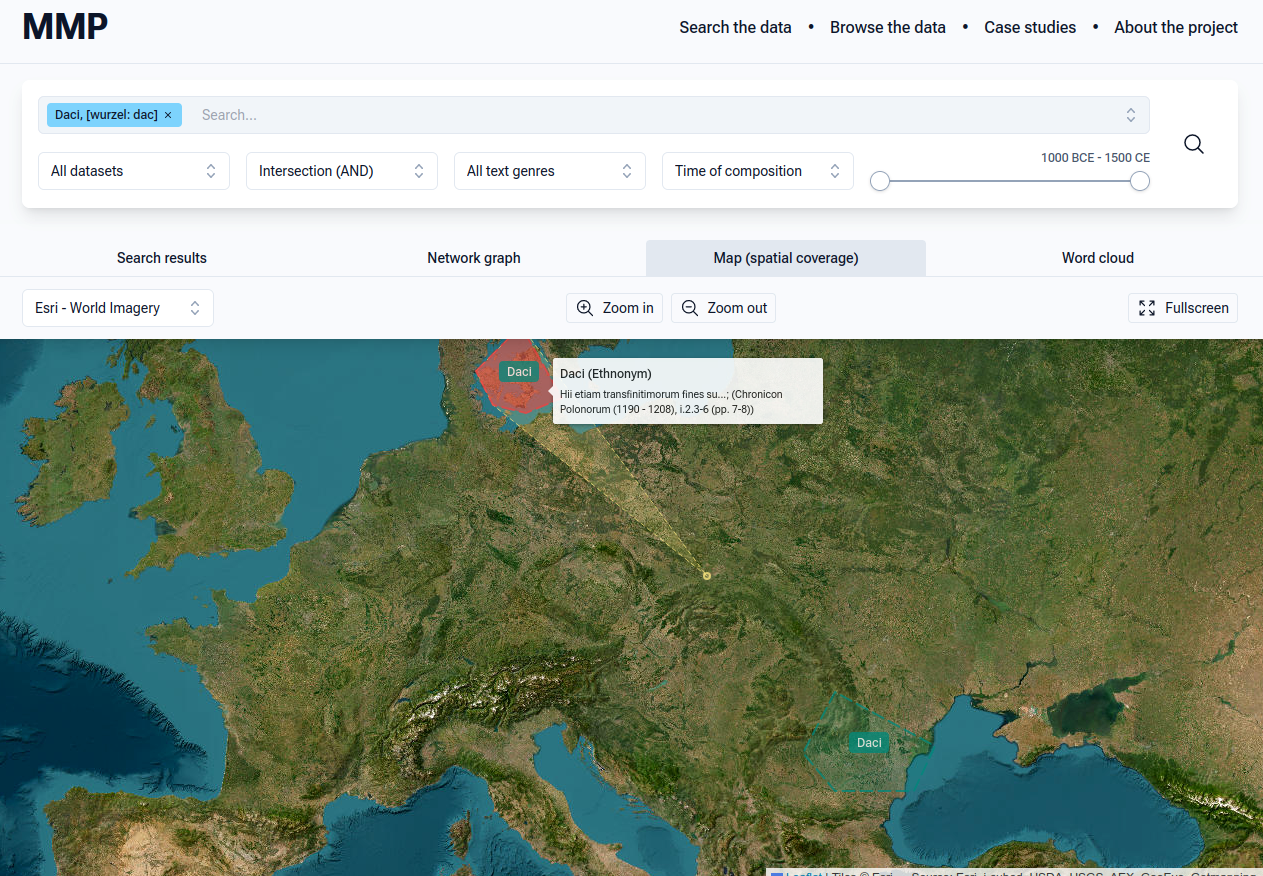

Not all saw it the same way though – writing only slightly later than Saxo, and also dealing with the legendary past, was the Polish chronicler and Bishop of Kraków, Vincent Kadłubek. He discusses an ancient defeat of a Danish king – here called Cnut, but possibly recalling ultimately his father, Svend Forkbeard, who was said to have been captured by Slavs – and claims that the victorious Poles then forced the Danes to choose between paying tribute in perpetuity, or else growing their hair long and dressing like women ‘as proof of their womanly unwarlikeness’. As the Danes took too long to make their mind up, they were forced to do both. Vincent then lifted an event from an ancient text, Justin’s epitome of Trogus, which says that the Daci – an antique term which many medieval writers re-applied to Danes, as a way of placing them within a classicising framework of peoples – after being defeated then had to sleep with their heads at the places where their feet should be, and the men had to do all the work that women would normally do, until this shame had been (somehow) expunged.

Vincent places these Daci on the ‘islands of Denmark’, so we can plot his perception of the Daci from those of the source he borrowed from, which has them in their classical location (see Fig. 5).

Just what led to this description of Danish cross-dressing and gender-bending may have been contemporary fashions – Danish men may have worn their hair longer and dressed differently to Poles, and this might have seemed, in Vincent’s eyes, a reason to concoct an amusing story which mocked the Danes as effeminate. If we turn back to Ailnoth, who I mentioned above, we also encounter a tale rooted in differing fashions.

Ailnoth had a strong dislike of the Normans and gives us some insights into tensions between the Anglo-Saxons and the ‘southern Normans’ – a term he uses to distinguish them from the Norwegians (both being Normanni in Latin) – whom he also refers to as Francigenae (French) and Romans. His Deeds of Svend (Estridsen) and Passion of Knud (the Holy), the first surviving ‘historical’ work written on Danish soil, probably shortly after 1110, tells of how in 1085 Knud hoped to liberate England by bringing it under Danish rule and restoring the empire of his grandfather, Cnut the Great.

But to return to hairstyles: the Normans wore their hair short, while English men, like the Danes, kept their hair longer and had beards. In order to make any invading Danish force think there were more Normans than there were, and also make it harder for them to identify who might be a sympathiser, William the Conqueror ordered English men to shave their beards and wear their hair in the Norman fashion, although Ailnoth says only very few actually did this.

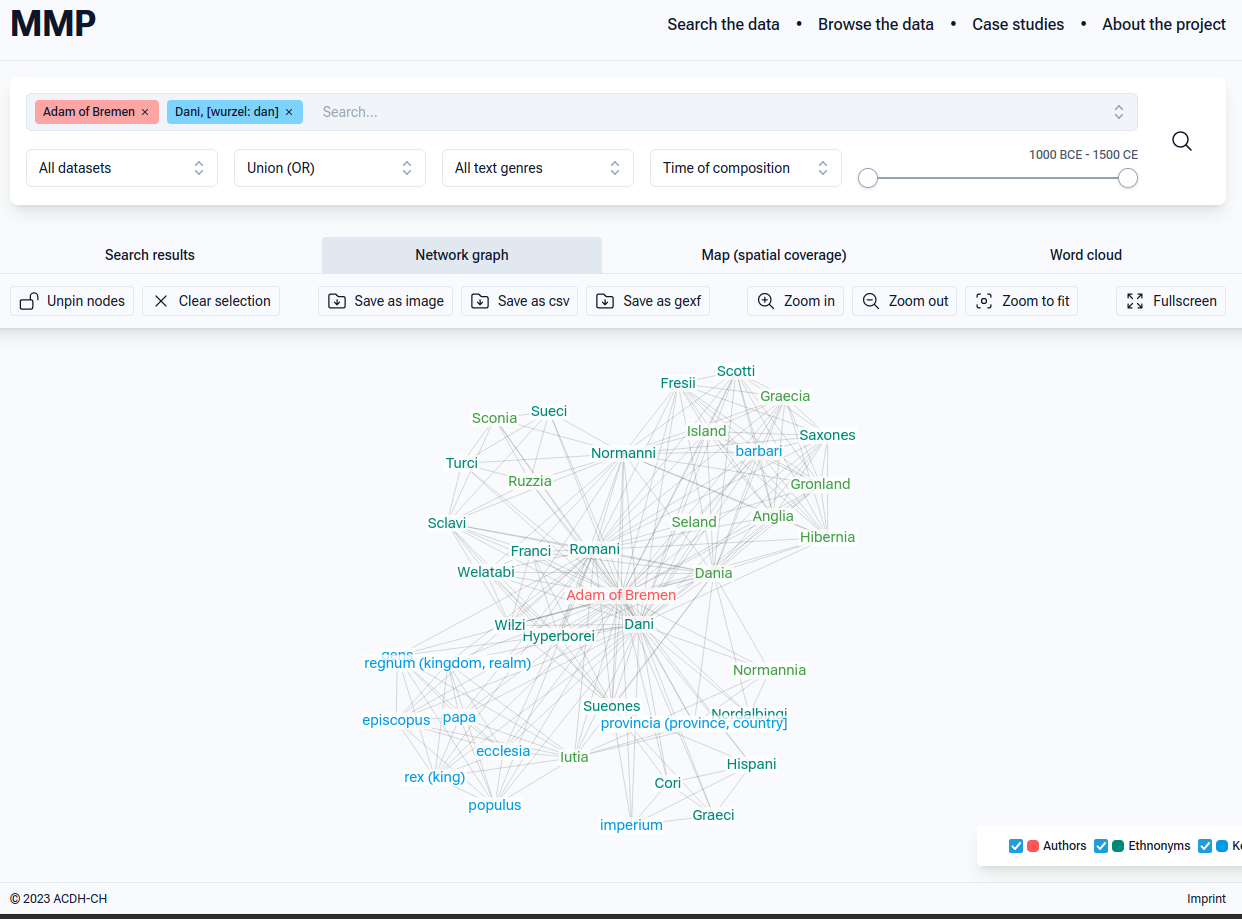

MMP gives us different options for visualising connections such as these – between texts, authors, keywords, regions and more. If, for example, we want to visualise the connections that result between various authors – let’s take Adam of Bremen here – we can put them both in, and see what passages or graphs come up, and filter them in various ways – both with a time-slider relating to the time of works composed, the events discussed in the passages, and with the option to search passages containing all search terms (AND) or any (OR) – so we can see the connections across a broader web (Fig. 6).

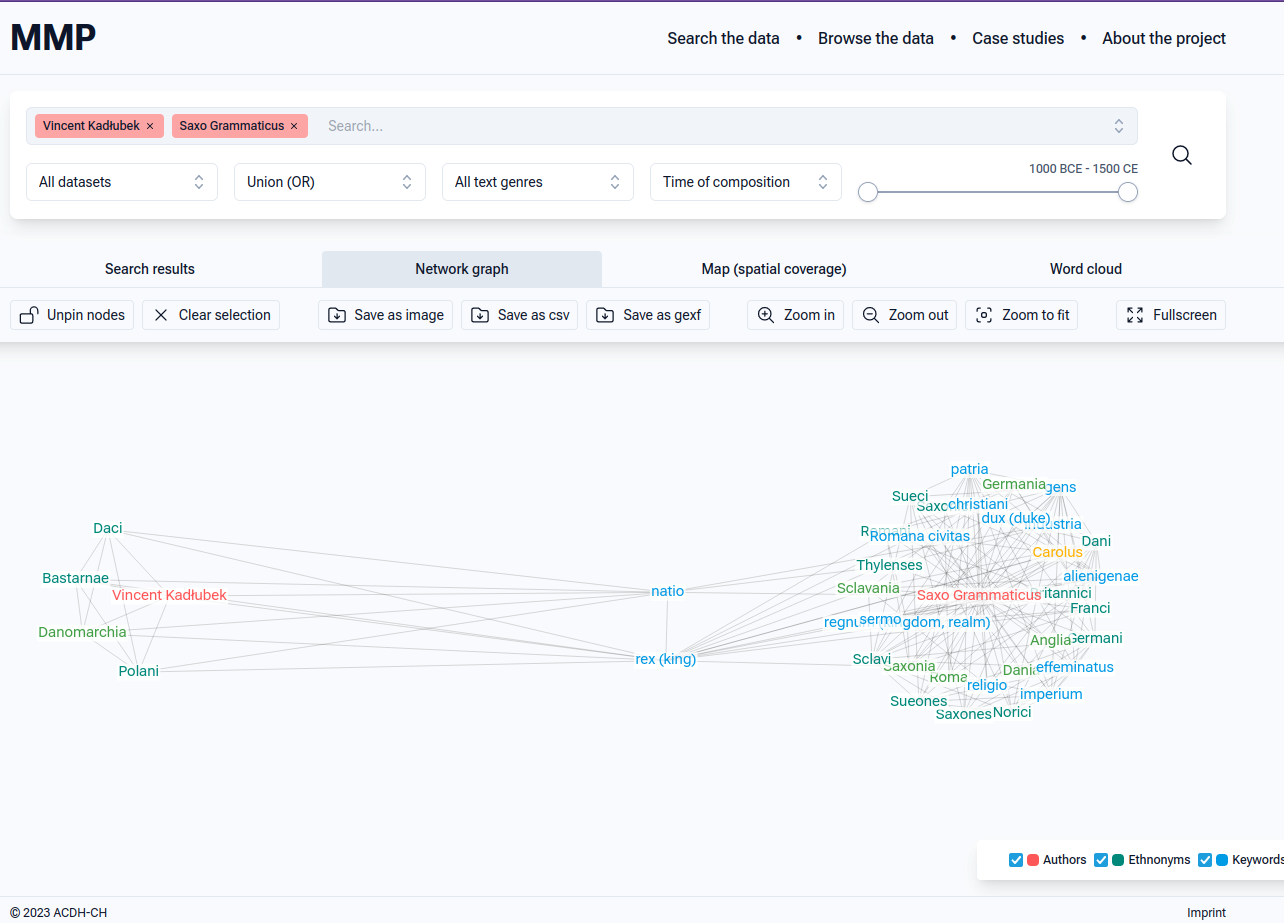

What I’ve wanted to track with my own study has been shifting perceptions of the north in different times and places, some of which I’ve discussed here: from fierce persecutors of Christians for Abbo, to imperfect Christians for Ailnoth, to practically natural Christians for Adam, to great warriors for Saxo – a view which was not quite, however, shared by Vincent. Incidentally, if we want to see a visualisation of the terms that Saxo and Vincent share and what connects them, we can also pull that up in MMP (see Fig. 7).

These are just some examples keyed to some themes that have come up in a specific case study – MMP will offer much more to explore, both in the form of specific case studies and from a larger database of texts drawn from the GENS database. Our site will be launched mid-2023 – keep an eye out for the announcements and you’ll be able to explore the data and try out our tools for yourself!