Tempo Effect and Adjusted TFR

The conventionally reported indicator of the level of fertility in a given calendar year, the period Total Fertility Rate or TFR, reflects the interplay of two components: tempo (timing) and quantum (level) of fertility. When the age at which women give birth changes, the TFR is affected by this shift. In Europe many countries have been experiencing a postponement of births (especially of first births) for several decades, which has also been reflected in an increasing mean age of childbearing. Childbearing postponement results in a decline in the number of births in a given year and therefore depresses the period TFR, even if the number of children that women have over their life course does not change. One can also think of this tempo effect in terms of an expansion of the interval between generations during which fewer births fall into each calendar year.

In order to come up with a measure of the level (quantum) of fertility that is free from the tempo effect and thus a better indicator for the average number of children per woman in a given year than the observed period TFR, the “tempo-adjusted TFR” has been developed. The adjusted TFR as listed in this data sheet is calculated on the basis of the Bongaarts-Feeney (1998) formula which uses fertility data by birth order. When available, the datasheet gives the mean of the adjusted TFR for the three-year period of 2003–2005. For countries where no such data are available the adjusted TFR is estimated either from the most recent available data or on the basis of an estimated relation of the observed change in the overall mean age of childbearing to the size of the tempo effect. (For a detailed description of methods and data see here).

Figure 1 illustrates the tempo adjustment for the Czech Republic where childbearing postponement was particularly pronounced after 1992 and the TFR fell sharply in tandem with an increase in the mean age at childbearing, reaching a low of 1.13 in 1999. Subsequently, it has ‘recovered’ somewhat and increased to 1.44 in 2007. However, the adjusted TFR reached a considerably higher level (1.78) in 2004–2006, indicating that most of the precipitous fall in the TFR during the 1990s was driven by a marked postponement of first births rather than by a genuine decline in fertility levels.

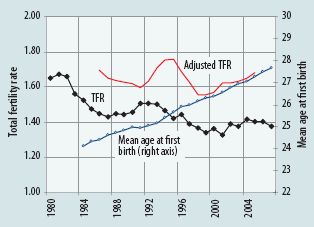

Austria provides an example of a low-fertility country with comparatively smaller fluctuations in the TFR during the last two decades. Fertility postponement has proceeded with a lower intensity there and consequently the gap between the TFR and the adjusted TFR is less pronounced (see Figure 2). In 1986–2005, the average TFR level was 1.42, whereas the average for the adjusted TFR was 1.64. So far there have been no signs of a diminishing of the tempo effect as shown by a continued increase in the mean age at first birth and the persisting gap between TFR and adjusted TFR.

This analysis suggests that the recent increase in the TFR in Spain should not be interpreted as a major turn in the fertility trend but rather as the expected consequence of the ending fertility postponement. The fact that the quantum of fertility also fell by so much indicates that many of the postponed births are not being recuperated. In many European countries between 2000 and 2006 the conventional TFR has increased somewhat, similar to Spain and the Czech Republic, and this increase is in part attributable to the diminishing tempo effect. The table above shows both the conventional and adjusted TFR for individual countries in Europe.